Transcript

Knott

. . . future generations to acquire some understanding of the Reagan Presidency and your role in it. We’re very grateful that you’re with us today. I think the first thing we should do, we usually do a voice ID for our transcriber, so if you could just introduce yourself.

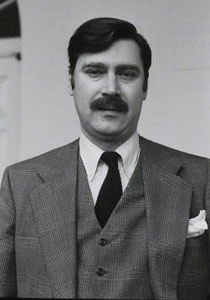

Bakshian

My name is Aram Bakshian. I’m here to be interviewed today as part of the Oral History Project on the Reagan administration.

Riley

I’m Russell Riley, an Assistant Professor at the University of Virginia, Miller Center.

Knott

And I’m Stephen Knott, an Assistant Professor and research fellow at the Miller Center. We usually like to begin by asking you how your career in politics began, if you could just take us back a bit. We notice that you are a lifelong Washingtonian?

Bakshian

Yes. My family always followed current events and we were Republicans. I was in the Young Republicans, at which point I then had my first actual political job, which was in 1966 when I was 22 and congressional staffs were expanded. So I was brought on for speechwriting, news releases, that sort of thing with then-Congressman Bill Brock, who was a Republican from Chattanooga who later was a Senator, later a Special Trade Representative, later Labor Secretary, et cetera.

Riley

How did you get connected with a Tennessean?

Bakshian

It was a matter of the D.C. Young Republicans. The actual urban population of Washington is overwhelmingly Democratic, so the D.C. Young Republicans consisted disproportionately of people who worked on the Hill or who were from elsewhere in the country, but then lived in D.C., often as Capitol Hill staffers. So it was a very Hill-centered thing. Most congressional staffs you’ll find over time, while they have a core of people from the constituency, the specialists and the Washington staff especially, as opposed to the district offices, tend to include a fair number of people who either had previous experience on the Hill or political experience or press experience, if that’s what they’re handling.

Knott

Speechwriting was part of your charge for Representative Brock?

Bakshian

Yes, that was the first political speechwriting I’d ever—well, the first speechwriting per se I’d ever done; I’d already done writing. And then from there, I was asked to do speechwriting for a few other people. There was in 1966, the midterm elections, a group, Americans for Constitutional Action [ACA], which was a conservative but mainstream organization, which endorsed candidates, and helped them raise money. It doesn’t play as large a role now, if it still exists. Also during the course of the campaign they would do what they called the

speech kit,

which was issued once every week for—I forget how many weeks, maybe it was ten speeches as the campaign heated up—prefab speeches that could go out to any candidate they endorsed, could be modified and delivered locally. There was a series: one on crime, one on foreign policy, one on budget, one on agriculture, et cetera. I was asked to do that, again by people I knew from being on the Hill and being in the Young Republicans.Those speeches reached just about every Republican Congressman, every Democratic Congressman who had a high ACA rating, and various candidates, some of whom ended up in office. Then some of them individually contacted me. So I accidentally became a speechwriter, as opposed to just an all-purpose writer, which I do on the outside. That was the entrance. And once you’re launched, it’s just like theater or being published, being in a decent production or having a good publisher. After you’ve had a book or two out then things take care of themselves a great deal more than when you’re on the outside trying to get in.

Riley

Had your family been involved in politics in Washington?

Bakshian

Not professionally, but they always had been active in the Republican Party and always followed current events quite a bit. The next major, full-time position I had, aside from speechwriting for this person and that, was in ’71. After the ’70 midterm elections, Bob Dole became chairman of the Republican National Committee [RNC], which meant that he had to have a second staff because if you’re a Senator and you’re also the chairman of the RNC, your Senate staff handles your Senate business but is not part of the Republican National Committee. So, as the new RNC chairman, Bob Dole needed a speechwriter. The chairman has to do a lot of speaking.

I was brought on as speechwriter for the chairman there on the basis of people who knew my work congressionally. I did that for about a year and some months. Bob Dole is not the easiest person to write for, because while he is a good impromptu speaker he doesn’t like using a script and he doesn’t like reviewing or editing. You get no insight on the way into writing it and either he takes it or he doesn’t take it, but there’s no insight about what he would have preferred to say or anything like that. So it was interesting and challenging, but mainly as a stepping stone to other things. Then again, all during this time I was also doing other writing for publication: history, criticism, reviews, et cetera.

The next big development came in ’72—this would have been maybe six months after I’d quit the RNC. I happened to do an op-ed piece in the New York Times as a conservative being critical of Congressman [John] Ashbrook’s run as a maverick against [Richard] Nixon in the New Hampshire Republican primary. He hadn’t run in New Hampshire yet, but he had announced his candidacy, at the same time that Congressman [Paul] McCloskey from California, the San Francisco area, was running from the left against Nixon in the primary. My point was that the Ashbrook ploy would be stupid because it would backfire, setting back the conservatives. Ashbrook would do so poorly, probably much worse than McCloskey, that if anything it would weaken the pressure from the right within the party, not strengthen it, and it was probably just a fundraisers’ delight more than anything else.

The squib at the end of my article identified me as having been a speechwriter for the chairman of the Republican National Committee, so people in the White House who read it—as I later reconstructed, I didn’t know this at the time—saw that I had a speechwriting background. They also saw it as a supportive piece and liked the way it was written. And it turns out they were just at that point getting ready to beef up the presidential speechwriting staff and were looking for some new writers.

About four or five days after the piece ran I got a phone call asking me to talk to a Mr. Clark, I believe in White House personnel, someone I’d never met or heard of. This was the first

make sure he has two arms and isn’t from Mars

interview. So I went and he explained that they were thinking of expanding the speechwriting staff. Then, I forget whether it was a week or two after that, I got a call from the office of Ray Price, who was the actual guy in charge of the speechwriting shop, which meant that the initial interview obviously had been favorable and they’d moved me up the next notch.Riley

You weren’t from Mars. [laughter]

Bakshian

That’s right. Or I was, maybe that’s what they were looking for. I met Ray Price and his young deputy whom no one had ever heard of at that stage of the game, named David Gergen, who I’ve known for years since. Then more waiting; they obviously were interviewing other people and so on. I forget what the lead time was between then and when I got the call to start, but I was brought on in late May or early June of ’72. So that was the entry at the White House level. Then I was subsequently the only Nixon speechwriter who actually was asked to stay on indefinitely in the [Gerald] Ford administration. Then of course we’ll be talking about the Reagan situation later.

Riley

Exactly.

Knott

So you were working with Pat Buchanan and William Safire?

Bakshian

I was actually next door to Pat Buchanan, but not when I first got there. When I got there in June, which I think was when I actually ended up starting, it turned out to be about a week before the Watergate break in. If I’d only known. I was working on the second floor. It was a makeshift arrangement where they just had to find space. They had added three people to the speechwriting staff. But once things settled in and they decided who was worth a damn and who wasn’t, I got a promotion and was kept when they thinned the staff out after the election. From then on, I was actually next door to Pat Buchanan.

This was either before he was harboring some of his more drastic current views, or the seeds hadn’t started fermenting in his head at that point, because he was just a very pleasant fellow, writing an occasional important speech. By the time I got there in ’72, the original head of speechwriting, a gentleman named [James] Keogh, who had been with Time magazine for years and had set up the operation, had left, at which point there were four fairly senior speechwriters besides secondary people. They consisted of Ray Price, Lee Huebner, Pat Buchanan, and Bill Safire.

When Ray Price was elevated to head the speechwriting staff, Huebner, Buchanan and Safire, since they’d all been co-equals before, were sort of given a senior status where they could write as much or as little as they wanted to. They were given one or two other responsibilities as well, but they weren’t doing the day-to-day grind. Thus Pat ended up in charge of the little sub-staff that did the daily news summary for the President and would occasionally write a speech, write political memos to the President and so on. Safire, I guess in retrospect, was leaking a lot to the New York Times in anticipation of building up a career there, and also wrote the occasional speech. But he, too, was semi-autonomous. Lee Huebner stayed more on the team, and I think also acted informally as sort of a deputy editor for Ray Price.

In any event, Pat happened to be next door to me. Also, we were both local boys; Pat was raised in Chevy Chase very close to where my mother was raised, just with different results.

Riley

He was a sort of young tough, wasn’t he?

Bakshian

No, he has that reputation. I think he would like to be remembered that way. As far as I know, he had no military or criminal experience—although he once kicked a policeman in the shin. I think that was the extent of his violent background. So when he talks about locking and loading or holding pitchforks, it has come to him rather late in life.

Knott

The kinds of speeches that you would tend to work on for President Nixon, was there a particular topic that they would send your way?

Bakshian

No. I came on with experience, in a sense, broader experience (a) because I’d also done outside writing on a number of topics, but (b) because I’d actually done speechwriting for people in national office. So that while at first obviously they try you with a few little things, by the time I’d been there a few months I wasn’t confined to light remarks. And I wasn’t brought on because I knew agriculture in particular or just economics. Some of that is beginning to happen more now than it used to, although you would occasionally get people on detail that were specialists. But you basically had senior writers and not-so-senior writers and in the end somebody might do more foreign policy writing or be called on to do the heavy duty domestic policy stuff, and some might be considered more political. But as you rose in esteem you really were a generalist rather than a specialist, so I’d written just about everything.

Riley

Were there other junior members of the speechwriting staff at the time? You said that there were—?

Bakshian

When I say junior, basically you had the people who were the full-time backbone speechwriters and then you had some sort of emeritus people who were still there and would occasionally write a speech but no longer had to produce a daily product. They would not be, for example, at the morning staff meeting or be part of the assigned work of the day and so on. I remember most of the names; I may have forgotten the exact head count.

When I joined in ’72 when they expanded, I was one of three new hires, consisting of myself, a fellow named Rodney Campbell, who passed away a few years ago who was born in England, but lived in America for quite some time and had worked for Nelson Rockefeller, either as Governor or as part of his public policy staff, because Rockefeller always maintained a presence on national issues. He may have almost been a balance hire to me as a Rockefeller Republican, since I was seen as a National Review conservative. Then one of the first women to be brought on ever as a presidential speechwriter, a lady named Vera Hirschberg, who had had some journalistic background. I’m not sure whether she had worked on the Hill at that time or whether it was basically journalistic, but she was a solid professional.

In addition to those three new people, you had a fellow named Jack McDonald, who was a veteran writer, a very tested pro who had previously I think worked for [Caspar] Weinberger at HEW [Health, Education, and Welfare].

Riley

Right.

Bakshian

Either that or he went there afterwards, but he had had some other political or policy experience. Then there was Noel Cook from Pennsylvania. I forget how he got there because he’d been there for several years before my arrival. And, of course, there was the celebrated Father John McLaughlin, who had been hired and was still a practicing priest, which proves that practice doesn’t make perfect.

Riley

Did he wear the collar?

Bakshian

Only on ceremonial occasions where it was the only way he’d get to an event, by saying grace. He had been a political hire, he had been an unsuccessful Republican candidate for Senate in Rhode Island, I believe. I think he was from Rhode Island.

Riley

I didn’t know that.

Bakshian

It was not a big race. Then he had worked, I think, for Postmaster General Blount as a speechwriter before he was brought on at the White House. Didn’t work out as a speechwriter, but it’s—

Riley

[Roy] Blunt?

Bakshian

I think it was Blunt, yes.

Riley

I’m from Alabama, and I have a hard time—

Bakshian

Well, I don’t know how long he was there. He was always working his résumé—

Riley

Sure.

Bakshian

He’s a good talker so he would make a good impression on the way in. He may have had a friend in White House personnel for all I know. But then, after doing one or two speeches, they decided that he wasn’t really one of our main strengths. However, you don’t just tell a priest that you’re giving him his walking papers. In fact, when Nixon resigned, the new press secretary, who didn’t last very long, Jerry terHorst, one of the first things he announced was that John McLaughlin was on his way out. But, before you knew it, Jerry terHorst had resigned and John McLaughlin was still there, hanging on with his teeth. And backed somewhat by [Alexander] Haig, for whatever reason. He did ultimately leave, but I think it was after they cut off the water to his office.

Then there was Lee Huebner, who although a senior writer was still an active and valuable part of the staff, and John Andrews who was a good writer and also happened to come from a Christian Scientist background. He did his job, he was totally qualified to be there, but he was thought to have a sort of inside track with [John] Ehrlichman and [Harry R. (HR)] Haldeman as co-religionists. There was a little bit of a factional thing there. Not factional really, but a Christian Science connection. It would be as if you had several Mormons working somewhere who all networked.

Riley

In the [George W.] Bush administration we’ve seen that, so—

Bakshian

It is interesting, these little marginal factors—they aren’t political, they’re cultural or religious. Oh, and there was one other fellow, who was I guess the youngest writer there—I was fairly young myself at 28, but he was I think in his early 20s. His name was Tex Lezar, and he had a strikingly good memory. He was very often pulling together anecdotes and support material. He would occasionally write remarks but not many major policy speeches. So that was the writing staff. Then of course there was also the research support and secretarial and administrative staff.

Riley

How was the dynamic inside? Was there resentment of the emeritus staff?

Bakshian

No, it was fine. After all, for people like myself, we were coming in, we hadn’t been part of the old thing so it wasn’t like they’d been jumped over our heads or anything. In fact, they hadn’t been jumped over anybody’s heads. Ray Price had been elevated in the sense that he had been singled out to take over the department, but they had all been compensated.

Riley

Right.

Bakshian

So it seemed to make sense. And it wasn’t as if the

seniors

were arbitrarily interfering or were rival power centers. In other words, if they were all supposed to be co-equals or something, that could have been difficult, but that wasn’t the case. Lines of authority were clear, so there wasn’t any friction. In fact, it was quite a happy department, very hard working. Indeed the Nixon White House was the best run operation I was ever a part of, in terms of day-to-day logistics and all. And until the Watergate business started getting really critical, it was a nice place to work. That is, if you were doing your job and were good at it, you knew your work would be recognized. There was pressure but it was pressure to perform.Occasionally it was a little unsubtle. On the day after the election, the 1972 landslide, everyone shows up for work and there’s a memo saying,

Everyone is being asked to submit a letter of resignation.

You’re familiar with this. And everyone did it. Even then, if you were fairly sure of yourself, after the first month or so there you knew where you stood. You could tell by the kind of assignments you were getting, first of all, whether you were considered up to snuff. If you were getting bigger and bigger assignments and then you were asked to go on Air Force One to attend an event or something, that was a pretty sure signal.So that when I submitted my

resignation

letter, I thought, I’m going to make the cut. I know one or two other people that I had my doubts about and indeed they didn’t. They were taken care of, they were given a chance to get something else in government, but that was just good management practice. It could have been done a little more subtly than asking for the letter the morning after the great victory celebration, but the choices were not factional. They were based on performance. I’d have to say that Haldeman, on the few occasions early on when I ever met him or talked to him, knew who you were, knew what your work was, and again, if you’d been delivering you had nothing to fear and there was nothing nasty about the way you were treated.It was a bit impersonal perhaps, but then again I was much more junior there than I was in the Reagan White House, especially at the beginning, when I was getting my first impressions.

Knott

I was just going to ask how much direct contact you had with President Nixon?

Bakshian

Not much. There’d be occasional meetings or signings, for example, and as I was promoted and writing the more important things, I would see mark-ups on major drafts when they were going back and forth, and occasionally even a little congratulatory note or call. Once or twice he may have called somebody whom he didn’t know but where he liked their writing. John Coyne, who joined from Vice President Agnew’s staff after Agnew resigned, was such a case.

But then again, Ray Price, who was in the equivalent position that I was under Reagan, did see more of Nixon. So for me to compare access as first a junior writer and then a fairly senior writer but not in charge, to my access to Reagan as his Director of Speechwriting, is not valid. But even with Ford, when I was at the same level I had been at the end of the Nixon administration there did tend to be a little more access to the Oval Office. That also had to do with the fact that [Robert] Hartmann, who was initially in charge of the speechwriting department under Ford, was in a rivalry with White House Chiefs of Staff and I think probably tried to maximize access for the one division that he was still in charge of, the speechwriters. So again, there may have been some Byzantine stuff involved. But Ford was also more open and a little more at ease. That was the nature of the individual personality, though.

Riley

You attribute a lot of the smooth running of the Nixon White House though to Haldeman’s management style?

Bakshian

Yes, because there were several people, we used to call them the clipboard boys, who were assistants. We mocked them, but they kept the trains running. There was a guy named Larry Higbee and another one whose name I can’t think of, but they were the ones that would show up frequently during the day to see how this was going or that was going. They were figures of fun at the same time that they were taken very seriously in terms of their power, but the bottom line was it was a very well-run operation, very professionally run as far as scheduling, as far as deadlines, coordination of information, and it all started with Haldeman. Not only that, but some of the things that made subsequent Republican administrations run well can be traced back to the structure of the Nixon White House.

If you chase down the political genealogy of people who are in there even now, some of the older ones might have been very young people in the Nixon or Reagan administrations. The Reagan administration had a leavening of people who had experience in the Nixon White House. That was one reason why, even though there had been a four-year interregnum with Democrats, the Reagan administration was able to set up fairly quickly and wasn’t swallowed by Washington. It was able to draw on people who had had part of an eight-year experience in power before.

Knott

By any chance, were you at the speech that President Nixon gave to the White House staff when he announced that he was resigning?

Bakshian

I happened to have taken the precaution, as it turned out, of being in Europe at the time. It was in the summer. Months before, I had scheduled three weeks of vacation. Because I had been commissioned, I think that was the year that I was doing a piece that would run two years later or so on the 100th anniversary of the Bayreuth Festival, so I was in Bayreuth, Germany, and then in Vienna, and in England on the way back. When I got back to Washington, I think it was either 24 or 48 hours after Nixon had resigned.

Of course I heard all the tales. Recently there was a TV documentary done on a friend of mine, Ben Stein, who was a new writer in the last months of the Nixon administration. One of the various questions they were asking me about Ben as they put the documentary together, which made it onto the documentary, was my mentioning that Ben’s always been very versatile. In fact, if you look at the footage of Nixon’s farewell speech to the White House staff, Ben, who is really a very versatile talent, is the only person in the entire room who is crying at the same time that he is chewing gum. He really is. There is this momentary shot of Ben chewing gum while the tears are running down his cheeks.

Riley

I want to go back and ask a question about the transition from writing for members of Congress, moving into a position of writing for the President of the United States. As a crafter of speeches, if you recall anything about your learning curve or about the kinds of lessons that you—

Bakshian

I think I understood on the way in. I mean, I’d been in Washington, I knew a fair amount about presidential rhetoric and I’d observed it, plus I’d written about history, diplomacy, culture, and whatnot. So you know enough to assume a slightly more magisterial tone. But the big adjustment in terms of how your work is affected is that the Hill is fairly loose and easy. There isn’t much in the way of a fact check staff. I mean, you look at it, maybe the senior assistant to the individual member looks at it, and the boss gives it or he doesn’t give it. Or if it’s connected with committee work, maybe someone on the committee staff drafts or reviews it, if it’s about detailed legislation.

At the White House, first of all you have your own research staff which is formally set up. This may have been an innovation under Nixon because Keogh, whom I mentioned as the first head of speechwriting who was gone by the time I got there, had worked for Time magazine. The research structure which he set up at the White House was based on the way Time would cover a story. That is to say, you didn’t have the identical number of researchers and writers, but each individual speech, whatever it was, big or small, was assigned to a writer and one of the researchers. She might be working on three or four at a time—in those days it was she, the writers were mainly he’s and the researchers were mainly she’s. But in any case, there was always a researcher and a writer assigned to each speech or set of remarks.

In addition, as drafts were circulated, the researcher usually followed the paper trail in the initial steps because the same speech might be circulated three times with re-writes and all. More than that sometimes, if it dealt with a very sensitive issue or a new policy. The researcher would keep track of all those mark-ups, and you would get them too. If it was a speech that dealt with a number of issues, domestic and foreign, for example, and legislative, you would have someone from the Congressional Liaison looking at it. Copies would go, if there were defense issues, to Defense, NSC [National Security Council], and probably State. Budgetary considerations to OMB [Office of Management and Budget], the whole speech would go, but that would be why they were supposed to be looking at it. Senior policy counselors would also get a whack at it. If farming, Agriculture, and so on. All that stuff would be fed back. The researcher would keep track of all this.

When they were just fact checks, it would be a matter of just making the corrections. When there were policy differences, very often the speech itself became a tool for negotiating what the final policy would be. So it was a much more elaborate, laborious, but also thoroughly interesting process from the time your first draft came out of the typewriter—forget about word processors then—to the moment of completion than it would have been on the Hill or almost anywhere else. It was actually more like a large multinational corporation, if you were writing policy speeches for the CEO, where there was an enormous bureaucracy that it had to filter through, which is why there are very few good speeches given by CEOs of large multinational corporations. Similarly you could say that very often with a President who doesn’t have a rhetorical flair, he’s in danger of being swallowed by the bureaucrats as far as the quality of his own utterances is concerned.

Riley

Did you find it difficult to adjust to writing within a bureaucracy? The impression I get is that most writers are—

Bakshian

I didn’t find it difficult to adjust. I didn’t particularly like it, but I wasn’t that surprised by it. It made perfect sense that that is the way it would be done at that level and it just came with the package. The people who are usually most frustrated by that are people who put all of their ego into writing for somebody else. They think of it as their speech rather than their client’s speech and then it is

how dare anybody touch it.

I don’t think that’s a particularly healthy attitude, or at least it wasn’t one that I was interested in embracing.Knott

You’ve already given us some indication, but could you talk a little bit about the differences between the atmosphere in the Ford White House as opposed to Nixon?

Bakshian

Well, the Ford Presidency first of all had not had—let me preface this by saying that I think President Ford altogether did a very good job and probably was the best person for that almost impossible time and place. I can’t think of someone who would have been better at the helm under the circumstances where he assumed office, which were probably the most negative, adverse, difficult circumstances any incoming President has ever had to cope with.I probably had less trouble adjusting from Nixon to Ford than some of my colleagues. I didn’t know Ford personally, but I knew people who knew him. I knew people that knew his staff. I had met one or two of the aides he brought with him, because the Hill was where a lot of his people came from. There were people I’d known when I was at the Republican National Committee or working for Brock, who were people who were at, say, the Republican Congressional Campaign Committee. For example, the first person who was in charge of speechwriting under Ford was named Paul Theis. He had previously been at the Republican Congressional Campaign Committee, where I had met him. I didn’t know him well, but I knew several people who had worked with him. So I was on more familiar ground than most of the other Nixon people.

Plus, as it happened, I and one other writer (John Coyne) had been detailed during the period when Ford was Vice President but not yet President and when he was just assembling his own staff, to help with some speeches. This meant that Hartmann, who was his Chief of Staff when he was Vice President, and who had come with him from the Hill, knew me and knew my work. He also knew I wasn’t obnoxious and trying to bully them as a presidential aide dealing with vice presidential staff. In other words, when the vice presidential staff was very much in the back seat, I had had a friendly collaboration with them and hadn’t been obnoxious and also had written things that they didn’t have to gag to swallow.

So that when Ford became President, I was not totally a stranger or just somebody who worked for the Nixon people. That may have been one of the reasons why I was the only Nixon speechwriter who was kept on long-term by the Ford White House, in fact until I unilaterally quit to accept a fellowship at Harvard more than a year later.

The Ford White House was the first Presidency in a long time that had to land running without ever having had a shakedown cruise. No campaign, no executive experience, although Jerry Ford knew Washington very well. And incidentally, of all the recent Presidents, I would say he understood the governmental process, the legislative process better than anybody since [Lyndon] Johnson. You would see this when a speech was being reviewed in the Oval Office, where he was going through it and they actually started talking about the nuts and bolts, not the rhetoric, but what was going to happen to this legislation. He knew where it was, how it would get through or wouldn’t get through; he thoroughly understood the process.

That isn’t something, unfortunately, that helps a person when they’re dealing with the public and communicating public concerns, because people don’t understand that or aren’t interested in it. But he was probably more competent in that respect than Nixon had been or than Reagan was on a detailed level. Ford also had a wonderful presence when you were in the Oval Office with him that was entirely different from what ended up being filtered through not only the TV cameras, but the people who edit the footage and concentrate on someone stumbling while descending from Air Force One.

He had a firm paternal, benevolent but authoritative way that worked very well when you were actually in the room and also when he was well-served with his speech material. His first speech to the nation couldn’t have been better. It was kept simple, but I think it restored confidence and sounded just the right note at a really bad time. We were still in an unpopular war and we’d never had a presidential resignation before. It can’t get much worse than that.

Riley

Were you involved in crafting that speech?

Bakshian

No, that was the last thing that was done exclusively, as it were, by his vice presidential staff headed by Bob Hartmann. I mean, he had just become President and then immediately the sorting operation began of whom to keep, whom to replace, and generally taking up the reins. As I say, I was the last

Nixon

tree standing in the speechwriting shop, as it turned out.Many people that ended up senior in the Ford White House weren’t really outside hires or people from the Hill. There were some, but many of them were junior, or second tier anyway, people who had been in the Nixon White House but who replaced the highly visible head of their division or office. Others were people who had Hill experience, like Don Rumsfeld, but who also had administration experience.

In the case of the White House writers, that was Hartmann’s surviving fiefdom with the result that it tended to bring more people in from the outside or the Hill. I was still there. John Coyne, another Nixon writer, was there for some months after the other people had left, but then he was replaced. As for the new hires, there were a few people from the Hill or people who had known Hartmann. Although there was one person who was hired because—I think Paul Theis, who was then heading the speechwriting office, thought that this was a very good friend of Hartmann’s. Actually Hartmann had I apparently received the résumé in a letter and forwarded it without being particularly concerned. But it was taken as,

Uh-oh, this is somebody we’ve got to deal with.

So there were a few accidents like that. And a number of people who were detailed, tested and didn’t last very long.When it settled in—and speechwriting was more like that than the generality of the White House—it was a pretty good staff. A lot of the same efficiency, since the structural machinery was already set up. It would be like a new officer taking over an army base but the army base is still running the way it had always run on a day-to-day basis. And that got it pretty much through the balance. The style at the top was quite different. Ford was more accessible. From a speechwriting point of view, he had more limited possibilities. Nixon was interested in big ideas, also until the last troubles, he had a big stage to perform on. Ford was an unelected President dealing with crises which were already in existence and he was bailing water, basically. There weren’t too many new initiatives that were going to go anywhere. So it was a less imaginative, creative time to be a speechwriter regardless of Jerry Ford’s admirable personal qualities.

Incidentally, I would refer you to an appreciation I did of Ford a year or two ago; it was in American Enterprise magazine where I described Ford in more detail.

Riley

Okay.

Bakshian

I forget the issue, but it would have an index.

Riley

Sure.

Bakshian

My article appeared right before Henry Kissinger’s, just by a fluke, but it must have really cheesed him off. But anyway.

Ford was very personable, but as a speaker, his style was somewhat more limited in terms of delivery. It wasn’t an intellectual problem. He was a sort of steady, slow speaker so you had less range. It would be like what sort of dialogue do you write for a certain type of actor. But the internal working, the mechanical working, the structural working of the White House under Ford wasn’t that different really from Nixon. It was almost an extension at the logistical and operational level. What changed was the personalities of the men at the helm and the circumstances, because suddenly it was a besieged White House with a Congress in opposition hands that had tasted blood and wasn’t going to give any fair chance where they thought they had an unfair advantage.

Riley

Was there discussion at the time of making clear breaks from the past in speechmaking practices or being more conciliatory, less combative?

Bakshian

I don’t recall there ever being meetings where people sat around and said anything like that, but you just understood that it was a new ball game. Ford’s role, especially initially, was to be a conciliator, heal the wounds and then try to govern. He also was faced with inflation as a major economic problem and of course what turned out to be the tragic end of the Vietnam war. And dealing with it with nowhere near the executive authority that his predecessor had enjoyed until the very end. So I would say the changes were externally driven rather than a matter of sitting around and coming up with a new idea. You were reacting to a different world out there. You had much more limited windows or targets of opportunity. There was only so much you could do. It was defensive, essentially.

Knott

So you stayed with President Ford until late ’75?

Bakshian

Yes. Just as when I first came to the White House, I had no agenda. Somebody reacted to something I’d written at a time when I didn’t even know they were looking for anyone. Similarly, I had met a few people who had fellowships at Harvard’s Institute of Politics. One of them had said,

By the way, you might just—you may not want to do it, but you might want to. I’d like to put your name in.

They ask former fellows to recommend other people. If they ask you to go up and talk to them, you go up to talk to them and see what you think and so on.So I said,

All right, go ahead.

They did ask me to come up and I liked the idea. Also, although I was in total sympathy, I had the feeling that as Hartmann’s last fiefdom, the speechwriting department was losing connection with the senior level. Some of the people that were coming in might have been calledold hacks.

Before, you always felt you were part of, I won’t saythe best and the brightest,

but there was some unit pride. There was a little less of that. There was very little reason to want to just hang on and stay there for the duration.Riley

Sure, sure.

Bakshian

I also had a feeling that if the Democrats didn’t totally botch it, they had an odds-on chance to recapture the White House in ’76, although an event devoutly not to be wished for in my view. But at the realistic level that’s where it looked like it was going. Also I looked forward to the idea of just taking a look at Harvard without having to actually go there as an undergraduate and listen to all the idiot professors. At Harvard. This is not a generic attitude towards professors.

Riley

No offense taken. [laughter]

Bakshian

So go to Harvard I did. Then when I came back, again I hadn’t planned it, but I became involved in two parallel political things. One was, as I mentioned at the outset, once you get started in this business and if your work is well received, then you hear from people or there are people that you worked with at one place who are now somewhere else and get in touch. Well, when I got back to Washington in early ’76, Dave Gergen had been working at Treasury with Bill Simon, who was a very dynamic, active Secretary of Treasury.

Simon also took his speeches very seriously, had a reputation for being difficult to write for, not in the Bob Dole sense of just having no ideas, but of wanting it just so and wanting a writer that he had confidence in. Part of it was winning his confidence. Once he had written somebody off, and he tended to do that about people who were professional Treasury staff, then I always felt—because I would occasionally get a draft that one of them had done, work a little on it—I would make some change, but I would say it was mainly their work. Simon would say,

Who worked on this?

And I would tell him who had prepared the first draft, which I had then edited and revised. Once he was sure I’d gone over it I think he looked at it in a different frame of mind than if it had just come to him directly from somebody who was one of the staff writers.Anyway, I ended up on a consultant basis doing lots and lots of work for him, although maintaining my freedom by not being an employee of Treasury. It was a contract arrangement.

Riley

Was he being viewed as a presidential possible that early?

Bakshian

At that point, no. There were some rumors about a vice presidential possibility but it was not really solid. No, that came later. That was after Ford was out.

Riley

And this was before he wrote his—

Bakshian

Oh yes, this was all before that, because this is when he was still in office as Secretary of Treasury. He started on the book while he was still in, but I think that wasn’t even really in gear until after the election. Because he’s still

lame duck

Secretary of Treasury until the January inauguration in ’77.Riley

Sure.

Bakshian

Anyway, so I was doing that. But in addition, during the actual campaign I was asked to come on and write. They had a battery of people at the Washington headquarters; we basically were responsible for writing statements, speeches, and speech inserts for prominent people around the country who were giving speeches. I remember one in 1976—Lyn Nofziger was there and he had worked of course closely with Reagan, and Reagan as you know had challenged Ford at the convention. This is the first time I ever wrote something for Ronald Reagan. It was just a tape that was made that then could be broadcast around. Nofziger was convinced that Reagan wouldn’t do it because of some of the shabby things that had happened to him during the Ford–Reagan rivalry. But when Reagan was reached directly, and this gave me an initial indication of the sort of person he was, there was no rancor and he was happy to do it.

That was the first time I ever wrote for him, sight unseen, I had never met the man. He made one or two little changes. I remember it was a phone hook-up, but I heard him deliver it, little knowing that this was the beginning of a long relationship. It was a very pleasant first impression.

So I was doing writing during the campaign, again as a paid consultant, and simultaneously doing unrelated magazine pieces and all that. Not about anything I was doing on the

inside,

just my own writing on humor, history, politics, and the arts. So after the election then, I took something at Union Carbide within about a year of that, yes, in ’77 or ’78. So ended my active engagement in politics until 1980.Riley

Were there any particular speeches either in the Nixon years or in the Ford years that you look back on that are notable? Any of your experiences that were noticeable, anecdotally?

Bakshian

Well, one or two things that can just give insights into how the process worked. The first big speech I wrote is not of any great historical importance but it sort of launched the post-convention campaign, because it was the first major speech he gave after the nominating convention in Miami. It struck the themes that were instrumental in that election because it was an address to the National Convention of the American Legion in Chicago. [George] McGovern had just spoken the day before and I was the writer assigned to it.

It’s not a matter of any particular lines springing to mind, but it coalesced the patriotic theme that allowed Nixon, who was never a particularly well-beloved figure, to actually be re-elected by a landslide and to win a large chunk of the votes of the blue collar Democrats who later would be called Reagan Democrats but in that year voted for Nixon. And who knows, in terms of political alignment, if it hadn’t been for Watergate, how much that alignment might have stayed in place rather than having to be reassembled. So there was that.

But just how speeches get written. For Nixon’s second inaugural, they wanted to do everything just right. So every writer was assigned,

Do your draft of what it should be like.

And unfortunately, everyone did. And Nixon, I don’t know whether he saw all of them or whether Ray Price or somebody else reviewed and sent highlights or what—but Ray Price ended up working with Nixon on the final product. Unfortunately Nixon saw some lines here and there that he liked from other speeches. As a result, it was a roller coaster speech with staple marks where you could almost—if you knew where these things had come from—identify things that had beenpasted in

from other drafts. If Nixon liked a penultimate line that sounded very good, he might use it, but in the middle of the speech.I remember one line that I had put in in connection with the Vietnam war, sort of a

don’t give up the ship

business. It sounds very good except historically it’s not true:There is no such thing as a retreat to peace.

I mean, that sounds very portentous, but it doesn’t mean a goddamn thing. Well, sure enough it cropped up in the middle of the speech with nothing before it that had any connection to what I had written and nothing after it. In fact, I remember thinking, Did someone drop that in by mistake? Did the cleaning lady forget to sweep up? And there were others I’m sure. I happened to spot that one because I recognized the line. The first time I ever was reminded of it was when he actually delivered the speech. But there were other instances like that because that was a case of having too many cooks. And that would happen occasionally.But it must be said, Nixon ordinarily, when he was focused and before the Watergate mess in the end, cared about his speeches. He would take time writing and drafting thoughts himself, sometimes wrote—and spoke on the radio, where people were not distracted by his physical appearance and the nervousness that showed up—with a clarity and an organization that was probably as good as any. He had a little more trouble humanizing, not because he wasn’t human, but because he was a very sensitive, private, uptight and bruised person in his own perception who wasn’t comfortable with his feelings. It wasn’t that he had no feelings. When you’re uncomfortable with your feelings you either bottle them up or when you do show them, it’s not in ways that make other people comfortable and that they identify with. But in terms of logic, structure and judging a good text, he was quite good. That was reflected in his mark-ups and his changes. It was intelligent editing.

I once was on a talk show—a public affairs one, not an entertainment one—with a fellow speechwriter. The subject was presidential speechwriting. It was a show that Mark Shield had on public television for a few years. This would have been toward the end of the [Jimmy] Carter years. Jerome Doolittle, a former Carter speechwriter, was the other panelist. During a break—he didn’t say it on the air—Doolittle said,

You know, in the two years,

or whatever it was he was in the Carter White House,I could never figure out what was worse: when you wrote something really good that Carter didn’t keep in the speech, or when you wrote something you thought was really good and he kept it in the speech and then you listened to him deliver it.

I don’t think it was that Carter intellectually misunderstood the content, he just had a quirky kind of delivery and the wrong word would be emphasized or the wrong sentence or the voice would soar when it wasn’t supposed to or it would trail off when it should have been going to the crescendo. But anyway, that was the big problem that that fellow had with his time there.

Riley

The music didn’t sound good on the other—

Bakshian

Yes, the feeling that I wrote that just to hear this guy murder it on the piano?

Knott

So you spent the bulk of the Carter years at Union Carbide, is that an accurate—?

Bakshian

No. It was one of those things—my advice to anyone is, if you’re offered a position and your first reaction is,

I can’t walk away from the money but I think this is going to be really dull,

my answer is, unless you’ve got heavy family medical bills or kids about to go into college or something, don’t take the job. Because if your first impression is it’s going to be dull, it’s probably going to be even duller. You may reach the point where you realize, God, there isn’t even anybody here I would like to have lunch with. So I was up there for about a year. Then what happened was a book project was revived. This had nothing to do with politics. It was memoirs of an old Austrian composer whom I’d known.Knott

The Waltz King?

Bakshian

Yes. I initially took a leave of absence, but as the nice fellow who was in charge of the division said,

You know, when you took that leave of absence I had a feeling we were never going to see you again.

Sure enough, I did contact them and explained,Sorry, but I won’t be back.

So the book project.Then, still in ’79, I was contacted to do a book on the upcoming 1980 presidential contenders, totally separate from this other book, and I did that too. Plus freelance writing and occasional speeches. I never set up a bureau or anything, but you get phone calls or someone asking for something. Also I was called on again, by people I’d known in the White House or at the Republican National Committee, to be co-editor of the 1980 Republican Platform. It was myself and Mike Baroody, brother of Bill Baroody, who were co-editors of the platform documents in Detroit at the ’80 convention. So that gave me the inside role, whereas my book on the candidates had also meant that I was out there being broadcast and whatnot on the subject.

That meant that even though I hadn’t worked on the campaign proper, when the transition began, there were plenty of people that knew me and I got calls and got involved, initially on the arts and humanities side of the transition team.

Knott

The book that you wrote, you predicted a Reagan victory, is that correct?

Bakshian

No, because it was written the year before and it was a matter of predicting who would get the nominations on both sides and speculating. It handicapped each candidate, what their strengths and weaknesses were, but it wasn’t actually saying who would win by how much, because it was written way before the conventions. In fact, I had to finish it before the first primaries, to give you an idea. What I did quite correctly predict, even though I was writing it months before the field had narrowed, was that it was going to end up being a Reagan-Bush match for the GOP and on the other side that while [Edward] Kennedy would be the only serious opposition, Carter would almost certainly be renominated.

The difficulty was at that point there were all these other irrelevant people in the field so you had to do chapters on people who didn’t deserve a footnote and had dropped by the wayside by the time the book was out. Larry Pressler I think was one of them, for example, and Phil Crane, the long-time Congressman from Illinois—I had actually ghosted a book on the Panama Canal for him several years before that.

There was an example of how ghostwriting is in Washington. I was asked to write the book; it was a quickie, a little under 200 pages—they may have laid it out in a way that went a bit longer—called Surrender in Panama. It was against the Panama turnover, the treaty. Well, I wrote it in a few weeks and when it came out I noticed that someone on the staff had added I think two footnotes. But it was almost verbatim the way it had been written. A friend of mine, who knew I did this and worked in Chicago, happened to be at a Republican fundraiser once where Crane was there, and a nice lady was coming up to Crane, a fan, and said,

Oh Mr. Crane, I so much loved your book on Panama and the thing I liked most about it, just reading it, I could tell you wrote every word of that yourself.

Actually the same friend had been on [Spiro] Agnew’s staff; he was a speechwriter, and one of the women’s magazines of the time—this was way before they got the way they are now—had asked for an article by Agnew talking about how he loved his wife, Judy Agnew. Agnew just assigned it to one of the writers. So this writer, John Coyne, wrote a nice article. And Agnew I think didn’t change anything. It was published, and he said what was sad was Mrs. Agnew was so touched by it, and assumed Agnew had written it himself.

Riley

Did you do other ghost projects, book projects?

Bakshian

Simon had asked me to help with his book but after some very initial work and being a house guest of the Simons for what seemed like two weeks, although I think it was more like ten days, I decided, Hmmm, I think somebody else might be more interested in this than I am. Total immersion with Bill Simon was more than I’d bargained for, though he was a remarkable guy, and very dynamic. He was disappointed that I didn’t want to stay on with that project, but he specifically asked that I still help with his speeches while he remained at Treasury, so we stayed on good terms. Maybe he respected me as one of the few people who walked away rather than just sat there and nodded.

The Memoirs of Robert Stolz, Vienna’s last waltz king, published as Servus Du in Germany, was written in his first-person voice, so that was a collaboration, although it was sort of along the lines of the Crane book in the sense it was taking tape recordings of his—it had started in ’73, and then he passed away in ’75. What happened was it was revived for 1980, which was his centenary. His widow was still very active, so, working with her, and taking tapes and the notes where we had left off, I brought the narrative up to the point where I had finished the research with him, in his voice, and then collaborated with the widow to cover the remaining years of their life together.

Riley

Did you write this in English or German?

Bakshian

Where there were German documents or phrases, I would use the German. I could deal with that. But I’m not a fluent writer in German so I was writing the main narrative flow in English. Both [Robert] Stolz and then his widow, Einzi Stolz, had English and she was very fluent.

Riley

I see.

Bakshian

She also worked with the German publishing house as they readjusted the final text. But wherever there was a source or a document that was in German I didn’t put it into English and then have them put it back, I would keep it in the original. Even the English I was writing in was idiomatic German. In other words, for an English language edition, almost all the dialogue and a lot of the expressions used would have been different. What I was doing was writing as a German, what would be close to a literal translation from the German idiomatically. Not just the expressions, but the tone, which was a bit different.

Riley

We can talk more about this during the break. I spent some time in Austria.

Bakshian

Charming little museum piece of a place. You know it’s going to be very interesting to see what happens as Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and other hungrier economies come on line because Austria is such a fat little welfare state. It’s a delightful place but I’m not sure how competitive they’re going to be in the out years.

Riley

This is where [Jurg] Heider gets his traction. But we can talk more about this during the breaks. Where did we—

Riley

Tail end of Ford, I guess.

Knott

And up to the ’80 platform. Was there a controversy associated with that platform?

Bakshian

Not really.

Knott

Were there unusual tensions between—?

Bakshian

There were some tensions but most of those were on the outside. In other words, there were some delegates on the floor who wanted to do this or that, but it was a fairly controlled convention because Reagan had clearly got the nomination. John Tower, then Senator, was chairman of the Committee on Resolutions, which is the platform committee. We knew what was going to end up being said, so it was mainly a matter of humoring people around the table who were the members of the committee, whether they were nice old Babbitts from somewhere who were delegates, or whether it was Jack Kemp, who was on the committee and who, to put it very mildly, is rather long-winded.

Riley

We’ve heard.

Bakshian

But it wasn’t rancorous. It was more a matter of just having patience and being able to store your urine while the monologues went on.

Riley

But that was a very conservative platform, even in comparison to the ’76 platform four years before, correct?

Bakshian

Yes, although platforms usually tend to be more doctrinaire, whether it is Democratic or Republican, and more controversial than the campaign message of the nominees themselves. This is especially true for the party out of power with no incumbent record to defend and less responsibility for official polity. They’re going to take a stronger line on the Middle East, usually for example on recognizing Jerusalem as the capital, and then whoever gets elected, usually then the State Department talks to them and they back off. In 1968 I remember, the Republicans were for the Ibos in the Nigerian civil war, being more against the official line and taking more humane interest in the rebel victims. Once the GOP was in, nothing changed. Same with Rhodesia. In that case it was a Reagan platform.

Today the 1980 platform probably wouldn’t read as particularly conservative because times have changed and the rhetoric is familiar by now. But on things like right to life and whatnot, in 1980 there were people who were predicting catastrophe and that it was an extremist document. As it turned out, (a) no one reads the platform, and (b) Reagan was not an alarming person and that’s very important.

Riley

Exactly. Whether Phyllis Schlafly had influence there or not.

Bakshian

The idea was that you let them get it all out of their system and some of it got into the platform. But again, you’re not talking martial law, confiscatory taxes or anything. I would say, what it was, there were some trigger words that the media, which was hostile to Reagan and generally hostile to the Republicans, would use to characterize the document as an extreme document. I would suggest that anyone who read it today would find it rather tame.

Riley

Sure.

Bakshian

Not at all controversial. Well, not particularly controversial.

Riley

But the political center of gravity had moved considerably to the right.

Bakshian

Had changed, that’s right. Most of the people that said it was an extreme document were the people that thought Reagan was unelectable, who never would have dreamt he was not only going to win the election in a very strong showing but that he was going to carry the Senate for the Republicans for the first time since the early [Dwight] Eisenhower years. So in a funny way, the platform may have been more in keeping with mainstream, Main Street public opinion than the pundits who were commenting on it as an extreme document.

Riley

Panama was also—or am I misremembering?

Bakshian

No, Panama was an issue that Reagan had used in the primaries to a certain extent. But it was far less of an issue than when he was running against Ford for the nomination in ’76.

Riley

Seventy-six.

Bakshian

Because it was a live issue then. By ’80 it was something that a number of people who had been against the treaty remembered and liked Reagan for again in the primaries, but it was a done deal.

Knott

So then did you go on during the fall to play a role in the campaign?

Bakshian

No, because the book was out. I didn’t think ethically there was a problem for the ten days or so involved in being up at the convention helping edit the document that would be the platform, as opposed to actually being in an advocacy role or out on the road with a candidate. Plus it’s not much fun. It’s interesting once. So I wasn’t involved in the campaign, although from the point of view of White House personnel and all, I had paid dues and participated because I had helped with the platform.

Instead, I was still doing commentary outside through the campaign and then was contacted after the election when they began the transition activities.

Knott

There was a point maybe a couple of times in the briefing book. You attended the victory celebration—?

Bakshian

Oh yes, because I described that in a piece for the—well, initially it was a piece for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, which I then expanded on as the introduction to a book called The Future Under President Reagan. It was sort of an anthology, it was a quickie that came out after the election but timed to come in about the time of the inaugural.

Knott

I wasn’t aware there was this spontaneous—

Bakshian

Oh yes, the ’80 election night enthusiasm I wrote about. Once it was clear Reagan had won, all of a sudden there was a flood of traffic into Washington. It was like people who had had it bottled up for a long time. And of course, they were much more likely to live in the suburbs than in D.C.. All of a sudden there was this traffic jam coming up to the Hilton, the same Hilton where Reagan was shot later but which was the campaign night headquarters. The place was mobbed by Middle Americans.

Knott

So how were you contacted?

Bakshian

Again, the overlapping. People talk about networking and all sorts of poor little souls consciously try to do it to no avail. The only real networks are the ones that are like the nervous system, already there for a reason. You’re not going to be able to install it yourself. A fellow who had been the editor at Arlington House Publishers, which was a conservative publishing house, who had called me about doing the book on the candidates, also ended up being involved in the transition. I don’t know how he had happened to, but he was there, including specifically the arts and humanities. He asked if I’d be interested in helping with that too, and I said fine. So I did. This was just going to occasional meetings, it wasn’t like dropping everything and moving into an office full time. There was a core staff that was full time. Also, as you can imagine, the arts and the humanities were not exactly on the top of the list in a transition when you’ve got foreign policy and serious domestic concerns.

So I was in the door. Then, I guess that meant that my name was on a list for that subject matter (arts and humanities) when the White House personnel started actually fleshing out the staffing of the White House. Elizabeth Dole was designated head of the Office of Public Liaison. A decision was made at that point to at least temporarily have one of her staffers deal with the arts and humanities in the large sense, education, the arts and all that. But also at this point, you’ve got lame ducks who are chairmen of the two endowments. Their terms aren’t over yet and the search is going to go on for replacements and it’s going to take a while, so it made sense to have someone in the White House, at least in the opening months, identified as point man for the arts and humanities. I agreed to do that. It was interesting. It was a painless way to return to the White House without any heavy lifting—I hadn’t aspired necessarily to go back to the White House and I hadn’t thought about speechwriting particularly.

So that was what I ended up doing initially in the Reagan White House. What led to the speechwriting was that Ken Khachigian, who had been in charge of speechwriting during the campaign and whom I had known in the Nixon White House initially, had told everybody that he had no intention of staying in Washington. He stayed a bit longer because when Reagan was shot he stuck around until the recuperation and the address to the joint session. But he had always told senior staff he was leaving. A lot of them don’t want to believe that. They think everybody desperately wants to be in Washington, so I think they didn’t really make early provision for replacing Ken.

So when he left, they didn’t really have a successor in place. They designated Tony Dolan, who was on the staff, to be acting head of speechwriting and that went on for some months. Apparently not to everyone’s satisfaction, because in the autumn of ’81 I got a call from White House Communications Director Dave Gergen. Initially, he didn’t say,

Will you take over speechwriting?

It was,We’re having real trouble hammering out a speech on the disarmament initiative, the arms reduction initiative. Could you just take some time?

And I was literally put in an office, a separate office from where my own office was, and given two drafts. Well, two-and-a-half really: a Defense Department draft and an NSC draft that had the State Department input as well as the Defense Department input.Of course they had been horribly messed up and were worded in bureaucratese and there were a number of things that hadn’t been reconciled. What they needed was a speech, a deliverable speech, which, even if some policy details still had to be hammered out, was written in a deliverable fashion and was ready for the President to look at rhetorically.

Riley

Sure. You had not written for Reagan since the radio address?

Bakshian

No, I hadn’t been writing speeches for anybody. Well, I had written speeches for other people in between, but I hadn’t been focusing on political speechwriting at all. But I happened to be in-house at a time when they were having trouble with a speech. Dave Gergen of course had worked with me in the late Nixon White House when Ray Price became sort of director emeritus and stayed on as a senior speechwriter with his own little office to deal with Nixon. Dave had then taken over the day-to-day running of the speech department. He had worked for Simon too so he knew me, he knew that I’d been able to write for Bill Simon—and actually be respected by Simon—so I think he figured Reagan would be no problem.

Anyway, I was a known factor. I was asked to do that and later asked to take over speechwriting. I forget how long it was before the formal announcement went out, but shortly after that speech I was put in. I told them at the time that I hadn’t orchestrated this and I didn’t have any long term aims for staying. I stayed longer than I’d planned. Again, I think they thought that once you land, you’ll stay. But that was how it happened. At least the first I knew of it was when I got the call to do that speech. Dave may have talked to [Michael] Deaver; they may have already been thinking about something like that. If so, I was both unaware and uninterested.

Plus, I was feeling increasingly that once the two endowment people were in charge, it didn’t make much sense to have a slot in the Office of Public Liaison, which is a very cosmetic outfit anyway, dealing with the arts and humanities. I mean, it’s mainly hand-holding with outside interests. There are real divisions and there are unreal divisions in any White House or any government agency. The standing joke in most corporations is that the human resources division is where you dump your leftovers. Usually, they’re never heard from again.

So when this came up I thought, Okay, do it for a while. The speechwriting staff was all in place. I didn’t fire anybody, I didn’t hire anybody. Some of them were better than others and I just made maximum utilization of the ones that were the best. With the ones that were not quite so good, I tried to find things they could do that they were capable of doing or that we had turn-around time to repair or touch up. And that remained true all the way through. Plus, most improved with experience.

I know from Deaver and the people who were close to the President, that the smoothest the speechwriting shop ever worked was when I was there, or so I’m told. Because there just weren’t problems. The prima donnas were kept under control and I was not a prima donna. As Director of Speechwriting, I had access to the President. That stopped at some point after I left because of human interactions between my successors and senior staff. It had nothing to do with the President changing his mind. And Mrs. Reagan was happy with the speechwriting shop on my watch. The way you knew Mrs. Reagan was happy was you never had to deal with her. The way you knew she wasn’t happy was if you suddenly did have to deal with her. But she felt he—the President—was well served by us.

Incidentally, she’s gotten a raw deal from people who complain about her interference. The only major intervention Mrs. Reagan ever made that I’m aware of happened after I was gone but I heard about it from insiders. The biggest disaster of the Reagan White House staff, not talking about overall administration, was making Don Regan Chief of Staff after the 1984 re-election. Everyone recognized it very quickly. But he was also a very ruthless person and everyone was scared of him, including the Vice President, and most of the senior staff. Mrs. Reagan was the only person who recognized the problem and acted on it. Of course, Don Regan then wrote a lot of nasty things about her.

As far as I’m concerned, the only times I know of that she ever injected herself—and it had nothing to do with speech content, because she thought he was being well served there—was if she thought the President was being over-scheduled. This had nothing to do with astrology and what day it was. It was working him too hard, dragging him out and making him catch too many planes and overnight in too many hotels and give too many speeches. In that little instance and in the big instance with Regan, not only was Mrs. Reagan’s

interference

justified, it was the right thing and it’s to her credit that she did it. Because someone had to do it and no one else had the guts to do it. Of course, she was uniquely positioned, it’s fair enough to say. Nobody else was married to the President at the time and Jane Wyman was not going to intervene. Riley: I find it of some interest that our colleagues in presidential studies actually recognized this. Richard Neustadt, who is sort of the dean of presidential studies, often speaks of theNancy function

and he has worked with us in consultation on our projects. We were talking about the current Presidency a couple of months ago and we asked him what does he think of the operations of this White House and so forth. He said,The one question, the one thing that I would most like to know about this White House is, who is serving the Nancy function?

So I think that it’s a role that you highlight, it’s not something that the public at large recognizes because she was such a—Bakshian

Also her husband was someone who didn’t like to fire, was a very amiable, nice man, and so she had to provide a little bit of the backbone. Not on policy, not on that, but on putting the foot down about human situations inside the household, as it were. Actually I think Laura Bush is like Mrs. Reagan, although an entirely different personality, just as George Bush is an entirely different personality from Ronald Reagan, yet there are certain parallels.

First of all, of recent Presidents, the Reagans and these Bushes—the old Bushes it was true of to a certain extent—are really close, tight. The husband and wife are a real team and a real marriage. They talk about things, live their lives together. Laura Bush, from what I can just reconstruct by studying the record and the biographical evidence, probably was the single person that had the biggest influence in turning her husband into a serious adult with a public sense of mission. She really turned his life around, because he always had leadership qualities in the sense that he was someone who knew how to bring out the best in other people’s performances and had a real gift of dealing with people, but he never really got serious until he gave up some of his extended adolescent habits of conspicuous consumption and whatnot, after she got hold of him. And I’ve got to think that where needed, she will always be there.

I do think that because of what he saw as Governor of Texas and also what he saw as his father’s son when his father was in the White House, where he in some ways did the Nancy function when he would come up on a visit—who is serving the President well, who is not?—he’s probably a little more attuned to that than the average President. He probably doesn’t need

Nancying

as much as most presidential newcomers. But were the need to arise, Laura would do it. Because everything that has happened so far, her blossoming as First Lady—she’s a private person with no lust for power or attentions, such an opposite of her predecessor—but when there is a need, she comes forward. Really, I can’t think of anyone who could do it better. She is the perfect contrast. She supplies certain human qualities that were drastically missing in her predecessor. And also in the very nature of the relationship of the previous President and First Lady, if it can be called that.And then, there’s her quality as conveyed when she is speaking on television. Laura Bush has the ability to be very, very articulate. I mean, on the Today show and other interviews, as well as where it’s scripted. I think she may surprise people before it’s all out. But I think her husband has a tighter grip and an understanding of what is going on in the shop, because although he didn’t work at the White House, he was there very often under his father and that’s precisely what he was keeping an eye out for then.

Knott

Let’s take a short break right now and we’ll resume in a few minutes.

Knott

Talk a little bit more about the Office of Public Liaison. Was there anything in particular during your brief tenure there, in terms of dealing with the arts community, that stands out?

Bakshian

Of course the arts community was in a great tizzy when Reagan came in. They thought the end of the world had arrived. So one did get calls and have meetings with some interesting people. Basically you were allaying fears, and as it turned out the world hadn’t really shattered and there was a budget fight and so on but things went on more or less as before.

I remember having a phone call from Isaac Stern. Also, there was an old European conductor, since passed away, Maurice Abravanel, who had been director of the Utah or the Salt Lake City Symphony, someone who had a lot of his recordings and he happened to show up, various other people like that.

Also, the in-fighting in particular for the National Endowment for the Humanities. There was a Texan named Professor Mel Bradford who had been a [George] Wallace supporter in years gone by, then had become a very conservative Republican. He desperately wanted to be Director of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Knott

Is this M. E. Bradford?

Bakshian

Yes. Mel Bradford. And a little bell went off in my head, This is a non-starter. It wasn’t a matter of my being opposed to him—I won’t say I could have cared less, but I didn’t have any agenda of my own. But I would be getting calls from him all the time. He would be lobbying conservatives on the outside. He was a very colorful man and probably was a very good actual professor to take a course from, because there were a number of bright younger people who had studied under him who were still very loyal to him. Some of them were now in the administration, even in the White House, and they didn’t want to say no to him, although I think in the back of their heads most of them knew this was not destined to be.

Bradford came up to town and he probably did the biggest favor he could have to the opposition. He went over and started personally campaigning on the Hill, going around talking to people. He hadn’t been named as the nominee or anything. Of course, the Washington Post wrote large pieces making fun of him, which didn’t require a great deal of skill. Anyway, he didn’t get it. The person who got it—it was the first in a stepping stone of other appointments—is a very well-known name today, and that’s Bill Bennett. He certainly wasn’t anyone conservatives could have objected to, although at the time there was grumbling from some of the Bradford partisans.

Riley

Were you at all involved in consultations about this particular appointment?

Bakshian

Yes, but I was just basically acting as honest broker. In other words, I was getting input, I just passed on candidate evaluations but it wasn’t as if I lobbied for anybody.

Riley

And were you passing these on to personnel?

Bakshian

Personnel and also senior people like Deaver and all who took an interest. The other thing which I took more pride in and which I kept when I went over to speechwriting, was the clearance process and the nominating process for the Medal of Freedom, which is the highest U.S. civilian honor. It doesn’t go for any one particular thing. In fact, while it’s usually a group presentation, sometimes, especially if it’s an older person who may not be around long, there will be an individual presentation. But about once a year or twice a year, they’ll give three to six at the same time. There might be one or two people from the arts, one or two humanitarians, somebody from medical science, a literary man, a great civil servant.

It’s an interesting thing because it’s the highest civilian honor. I took it very seriously. But at times there are going to be people who have been big contributors or something, who are really pushing for it and it’s important that somebody be a gatekeeper for that. In fact, after I left, I realized that—I’m not going to name any names—but one or two people, who had spent a lot of money and been humanitarians but not all that distinguished, but also had spent a lot of money contributing to candidacies, finally got in. These were people I’d managed to fend off while I was there, but then they crept through. Also people who had had some accomplishments but I didn’t think were quite up to the Medal of Freedom but who later on got in.

Conversely, people ask me, what do I think my greatest achievement was in my years working at the White House? And I always say,

I finally got Eubie Blake the Medal of Freedom.