Richard Nixon: Domestic Affairs

The Nixon administration marked the end of America's long period of post-World War II prosperity and the onset of a period of high inflation and unemployment-"stagflation." Unemployment was unusually low when Nixon took office in January 1969 (3.3 percent), but inflation was rising. Nixon adopted a policy of monetary restraint to cool what his advisers saw as an overheating economy. "Gradualism," as it was called, placed its hopes in restricting the growth of the money supply to rein in the economic boom that occurred during Lyndon Johnson's last year in office.

But gradualism, as its name implied, did not produce quick results. As the congressional election year of 1970 began, Nixon, according to Haldeman's diary, repeatedly asked the chairman of his Council of Economic Advisers "to explain why we hadn't solved the inflation problem." The President also said "that he never heard of losing an election because of inflation, but lots were lost because unemployment or recession. Point is, he's determined not to let the war on inflation get carried to the point that it will lose us House or Senate seats in November." Political concerns would play an overriding role in the economic decisions of Nixon's first term.

Nixon's fears proved well-founded. By the end of 1970, unemployment rose to the politically damaging level of 6 percent. In that year, Nixon appointed his chief economic adviser, Arthur Burns, chairman of the Federal Reserve; Burns quickly asserted his independence by giving the President an ultimatum: if Nixon failed to hold federal spending under $200 billion, Burns would continue to keep the money supply tight to fight inflation. Nixon acceded to Burns demands. To save money, he delayed pay raises to federal employees by six months. One result was a strike by the nation's postal workers. Although Nixon used the U.S. Army to keep the postal system going, he ultimately yielded to the postal workers' wage demands, undoing some of the budget-balancing that Burns demanded.

Nixon found himself entering the congressional campaign season faced with unemployment, inflation, and Democratic demands for an "incomes policy" to check spiraling prices and wages. Some called for wage and price controls. In the fall, Republicans picked up two seats in the Senate but lost nine in the House, a development that Nixon blamed on the economy.

The economy continued to deteriorate. By the middle of 1971, unemployment reached 6.2 percent while inflation raged unchecked. Nixon decided his administration needed a single economic spokesman and tapped Treasury Secretary John Connally as its mouthpiece. Connally made sweeping statements about the President's intentions: "Number one, he is not going to initiate a wage-price board. Number two, he is not going to impose mandatory price and wage controls. Number three, he is not going to ask Congress for any tax relief. And number four, he is not going to increase federal spending."Within a matter of weeks, the Treasury Secretary and the President would reverse course. In August 1971, Nixon gathered all of his economic advisers at Camp David and emerged with a New Economic Policy that stood the old one on its head. The NEP violated most of Nixon's long-held economic principles, but he was never one to let principle stand in the way of politics, and his dramatic turnaround on economic issues was immediately and enormously popular. One participant in the Camp David meeting, Herb Stein, thought the assemblage of advisers "acquired the attitude of scriptwriters preparing a TV special to be broadcast on Sunday evening." The announcement had to be as dramatic as possible. "After the special," as Stein put it, "regular programming would be resumed."Nixon came up with a smash hit. He announced a wage-and-price freeze, tax cuts, and a temporary closure of the "gold window," preventing other nations from demanding American gold in exchange for American dollars. To improve the nation's balance of trade, Nixon called for a 10 percent import tax. Public approval was overwhelming.

Nixon then became the beneficiary of some good luck. An economic boom, which began late in 1971, lasted well into the 1972 campaign season, long enough for Nixon to parlay its effects into reelection that November.

The downturn resumed, however, in 1973. Expansive fiscal and monetary policies combined with a shortage of food (aggravated by massive Soviet purchases of American wheat) to fuel inflation. And then came the oil shock. Oil prices were rising even before the onset of the Arab oil boycott in October of 1973. Ultimately, inflation would climb to 12.1 percent in 1974 and help push the economy into recession. When Nixon left office, the economy was in the tank, with rising unemployment and inflation, lengthening gas lines, and a crashing stock market.

Regulation and Social Legislation

"Probably more new regulation was imposed on the economy," wrote Herb Stein, the chairman of Nixon's Council of Economic Advisers, "than in any other presidency since the New Deal."The federal government took an active role in preventing on-the-job accidents and deaths when Nixon in 1970 signed into law a bill to create the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). That same year, rising concern about the environment led him to propose an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and to sign amendments to the 1967 Clean Air Act calling for reductions in automobile emissions and the national testing of air quality. Other significant environmental legislation enacted during Nixon's presidency included the 1972 Noise Control Act, the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, the 1973 Endangered Species Act, and the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act.

Despite this blizzard of legislation, environmentalists found much to criticize in Nixon's record. The President impounded billions of dollars Congress had authorized to implement the Clean Air Act, lobbied hard for the air-polluting Supersonic Transport, and subjected environmental regulation to cost-benefit analyses which highlighted the economic costs of preserving a healthy ecosystem.

Nixon proposed more ambitious programs than he enacted, including the National Health Insurance Partnership Program, which promoted health maintenance organizations (HMOs). He also proposed a massive overhaul of federal welfare programs. The centerpiece of Nixon's welfare reform was the replacement of much of the welfare system with a negative income tax, a favorite proposal of conservative economist Milton Friedman. The purpose of the negative income tax was to provide both a safety net for the poor and a financial incentive for welfare recipients to work.

Nixon also proposed an expansion of the Food Stamp program. His Family Assistance Program was bold, innovative-even radical-and, apparently, insincere. "About Family Assistance Plan," Haldeman wrote in his diary, the President "wants to be sure it's killed by Democrats and that we make big play for it, but don't let it pass, can't afford it." One part of Nixon's welfare reform proposal did pass and become a lasting part of the system: Supplemental Security Income (SSI) provides a guaranteed income for elderly and disabled citizens. The Nixon years also brought large increases in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid benefits.

Watergate

Watergate was so much more than a single crime and cover-up that it is impossible to summarize the tangle of abuses of presidential power that today are grouped under the name of the hotel where the Democratic National Committee had its offices. The arrest of five men in those offices on June 17, 1972, was the first step toward unearthing a host of administration misdeeds. It was to hide those other crimes that Nixon and his men launched the cover-up, the investigation of which helped to unravel that string of illegal conduct.

Watergate was so much more than a single crime and cover-up that it is impossible to summarize the tangle of abuses of presidential power that today are grouped under the name of the hotel where the Democratic National Committee had its offices. The arrest of five men in those offices on June 17, 1972, was the first step toward unearthing a host of administration misdeeds. It was to hide those other crimes that Nixon and his men launched the cover-up, the investigation of which helped to unravel that string of illegal conduct.

Indeed, Watergate was far from the first break-in. A year earlier, Nixon had unconstitutionally created his own secret police organization, the Special Investigations Unit, to unearth a conspiracy that he feared would leak some of his most damaging foreign policy secrets, including the secret bombing of Cambodia and Laos. The President, however, could not convince FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover that such a conspiracy actually existed. Nixon also wanted to expose the alleged conspiracy in the press, something the Justice Department could not legally do. He decided he needed his own team to investigate the conspiracy and leak damaging stories about it. Thus was born the SIU, better known by its nickname, "The Plumbers," an inside joke about its mission to fix leaks.

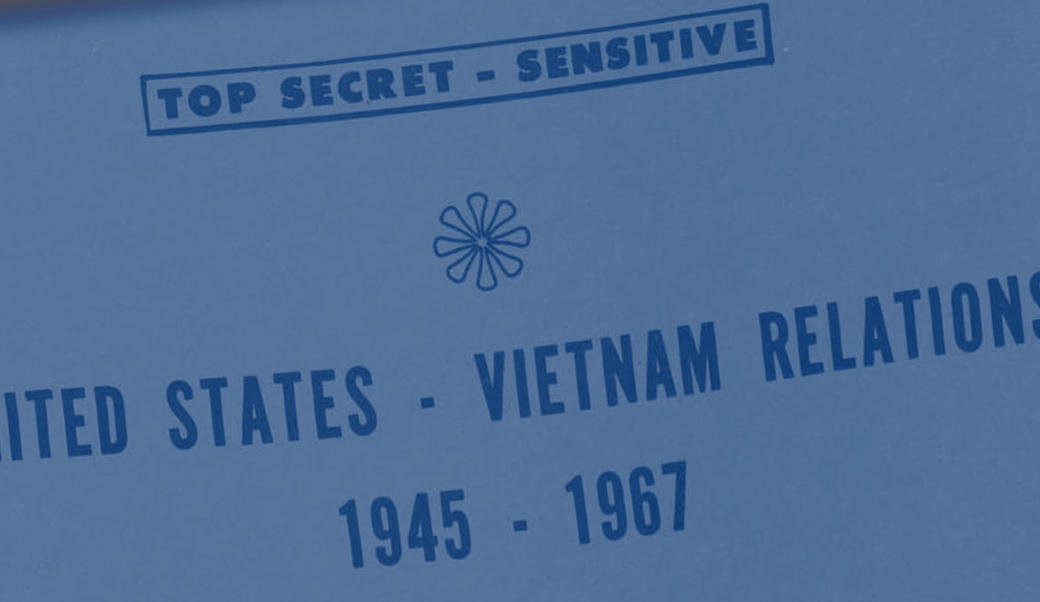

The immediate cause of Nixon's concern was the publication of the Pentagon Papers, a massive study of the Vietnam War as it was conducted by Nixon's predecessors. The study was commissioned by Robert S. McNamara, the secretary of defense under Kennedy and Johnson. It did not contain a word about the Nixon administration but it did reference top secret documents from the two prior presidencies. The leak ignited Nixon's fear that his own politically damaging secrets would be exposed before the 1972 election. He suspected a conspiracy and resolved to destroy it before it destroyed him.

It was to find out more about this imaginary conspiracy that two of the Plumbers, ex-CIA agent E. Howard Hunt and ex-FBI agent G. Gordon Liddy, planned and carried out an operation to discredit Daniel Ellsberg, the man who leaked the Pentagon Papers. Hunt and Liddy burglarized the offices of Ellsberg's psychiatrist, looking for damaging information on the former Pentagon aide and military operative. Hunt recruited the break-in team through members of the Cuban expatriate community in Florida he knew from his time as a CIA agent working on the Bay of Pigs invasion. When some of those same Cuban expatriates were arrested in the Watergate complex, and when it was discovered that Hunt and Liddy were behind the Watergate break-in as well, Nixon sought desperately to cover up their earlier misdeeds.

In fact, it was his concern with those earlier transgressions that gave rise to a post-Watergate political axiom: that the cover-up of the crime can be more damaging than the crime itself. Nixon's creation of a secret police organization without congressional authorization—one that carried out an illegal break-in without a warrant, no less— would ultimately become a basis for one of the articles of impeachment brought against him by the House Judiciary Committee. As Howard Hunt would put it in an angry memo as his prosecution moved forward, "The Watergate bugging is only one of a number of highly illegal conspiracies engaged in by one or more of the defendants at the behest of senior White House officials. These as yet undisclosed crimes can be proved." Nixon's chief aide, Bob Haldeman, was caught on tape alluding to this very issue:

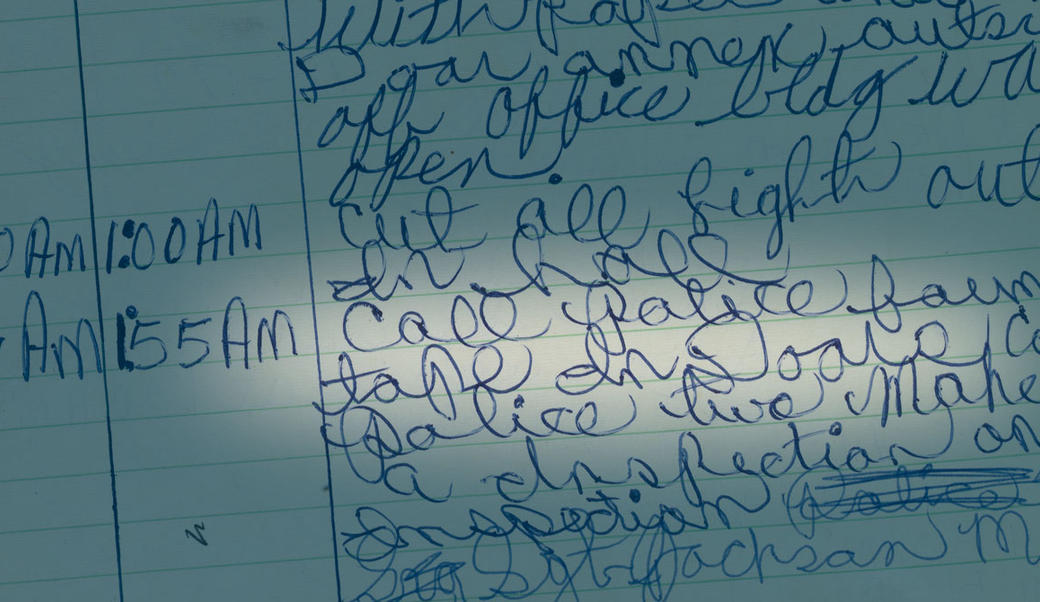

Haldeman: The problem is that there are all kinds of other involvements and if they started a fishing thing on this they're going to start picking up other tracks. That's what appeals to me about trying to get one jump ahead of them and hopefully cut the whole thing off and sink all of it. [June 21, 1972, quoted in Stanley Kutler's Abuse of Power]

The hope of cutting off the investigation led, two days later, to the conversation between Nixon and Haldeman that became known as the "smoking gun" tape when the White House released it under court order in 1974. In this exchange, Nixon decided to have the CIA tell the FBI to, in Haldeman's words, "Stay the hell out of this." Nixon suggested that the CIA say that "the problem is that this will open the whole, the whole Bay of Pigs thing, and the President just feels that, ah, without going into the details—don't, don't lie to them to the extent to say no involvement, but just say this is a comedy of errors, without getting into it, the President believes that it is going to open the whole Bay of Pigs thing up again."

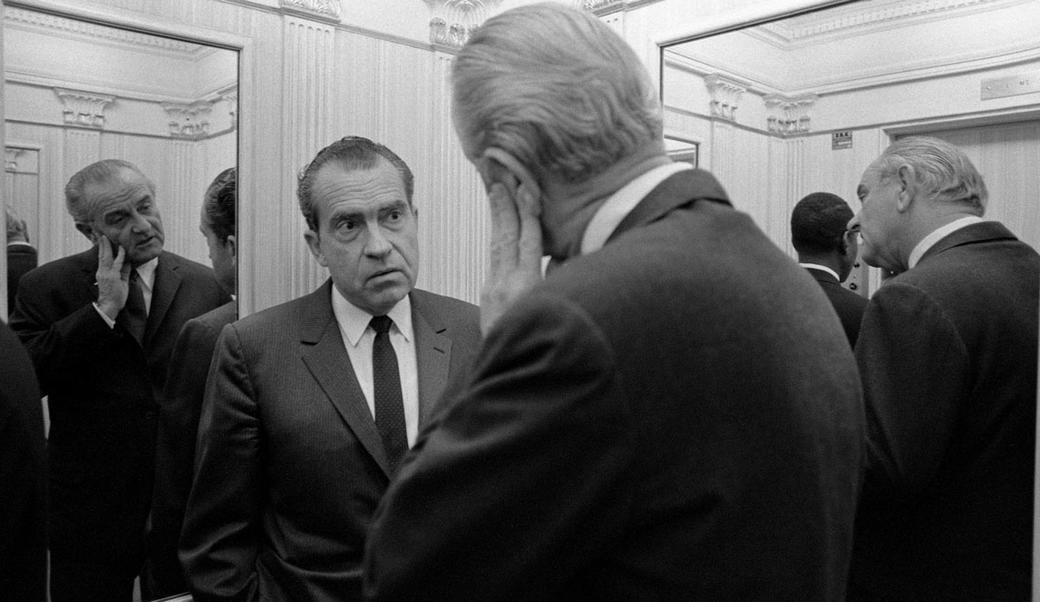

The White House managed to prevent Watergate's political fallout from affecting the 1972 election. But Nixon had hardly begun his second term when the dam broke. In February 1973, L. Patrick Gray, Nixon's nominee to succeed the late J. Edgar Hoover as head of the FBI, revealed during his confirmation hearings that he had allowed John W. Dean, a White House legal counsel, to sit in on FBI interviews of Watergate suspects. Nixon refused to allow Dean to testify before the Senate Watergate committee chaired by Sam Ervin (D-N.C.), citing the doctrine of executive privilege. Gray's nomination was all but dead.

"Let him hang there," John D. Ehrlichman said memorably. "Let him twist slowly, slowly, in the wind."At the sentencing hearing for the Watergate burglars on March 23, 1973, Judge John J. Sirica read a letter from James McCord, an ex-CIA man and the security chief for Nixon's reelection campaign until his arrest in the burglary. The letter made four points:

1. There was political pressure applied to the defendants to plead guilty and remain silent.2. Perjury occurred during the trial of matters highly material to the very structure, orientation, and impact of the government's case, and to the motivation and intent of the defendants.3. Others involved in the Watergate operation were not identified during the trial, when they could have been by those testifying.4. The Watergate operation was not a CIA operation. The Cubans may have been misled by others into believing that it was a CIA operation. I know for a fact that it was not.

The investigation began to close in on Dean, who, unbeknownst to the President, decided to turn state's evidence. By the end of April, Nixon announced the resignations of Dean, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman. The next month brought the Senate Watergate hearings, televised and widely watched. As witness after witness revealed more details about scandals old and new, Nixon's approval rating sank like a stone. One witness, Alexander P. Butterfield, a former Haldeman aide who then headed the Federal Aviation Administration, revealed the existence of Nixon's White House taping system. Objective evidence existed to determine who was telling the truth—the White House or its accusers.

Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox subpoenaed the tapes. In October, Nixon fired Cox, a move that prompted the resignations of Attorney General Elliot Richardson and his deputy, William Ruckelshaus. The "Saturday Night Massacre," as it quickly became known, backfired on Nixon. The outrage it inspired among the American public led him to reverse course and agree to turn over the tapes to Judge Sirica. A new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, was appointed and subpoenaed 64 more tapes, including the July 23, 1972, "smoking gun" tape. Jaworski took the case all the way to the Supreme Court, which voted 8-0 to uphold the subpoena. With the release of the tapes, the bottom fell out of Nixon's political support. Senator Barry Goldwater, the conservative leader, told the President that there were a maximum of 18 senators who might vote against his conviction on the articles of impeachment—too few to save him. The Nixon presidency was over.

Nixon announced his resignation on August 8, 1974, to take effect at noon the next day.

In his inaugural address, incoming President Gerald R. Ford declared, "Our long national nightmare is over." One month later, he granted Richard Nixon a full pardon.