The Biden era begins

UVA Institute of Democracy experts assess the latest developments as the new president settles into office

VISIT ‘ELECTION 2020 AND ITS AFTERMATH’ FOR OLDER POSTS

This effort is made possible thanks to the generous support of the George and Judy Marcus Democracy Praxis Fund

‘IT'S ENTIRELY UP TO THE SENATE’

Miller Center scholar Ken Hughes, an expert on the Nixon presidency and presidential abuse of power, discusses the second impeachment of Donald Trump with ABC Australia's Fran Kelly

January 26, 2021

EXECUTIVE ORDERS, IMPEACHMENT, AND OSHA

Former Obama administration official Chris Lu, now a Miller Center senior fellow, joins Sirius-XM's Julie Mason to talk about key issues during President Biden's first week

January 25, 2021

‘THE CURRENT MOMENT WOULD NOT HAVE BEEN FOREIGN TO THE FOUNDERS’

Miller Center Director William Antholis sits down with his brother Kary to discuss the second impeachment of Donald Trump

January 23, 2021

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM BIDEN'S COVID-19 PLAN

Two Miller Center experts, J. Stephen Morrison and Guian McKee, join UVA Law's Margaret Riley to assess the new administration's first moves

January 22, 2021

Executive orders to address the Covid-19 pandemic were among the critical first move of the Biden administration. During a public forum, Miller Center experts reviewed the plans, and offered these assessments. The entire webinar is available below.

1) Vaccination supply and the Defense Production Act

Coming into office, Biden announced a goal of vaccinating 100 million Americans in his first 100 days in office. Riley called this goal “both an ambitious plan and probably an undersell.”

“If we can meet 1 million doses a day, we will meet that goal easily,” she said. Currently, the U.S. is nearing 1 million doses per day; Riley said getting there and staying there will depend on other issues, including the Biden administration’s use of the Defense Production Act and organizations like the Federal Emergency Management Agency or the National Guard to distribute the vaccine.

2) The relationship between federal, state, and local governments

Both Morrison and Riley pointed to gaps between federal, state and local governments as a major cause of confusion and delay in the first month of America’s vaccine rollout. “This assumption of national federal responsibility marks a dramatic change from the Trump administration,” which had tended to shift those decisions to the states, Morrison said.

3) Equity and Justice

“We have seen a significant degree of inequity across racial lines in particular, as African Americans and other minority communities have suffered more than other Americans throughout the pandemic,” McKee said, “and that is something we are starting to see emerge in the ongoing vaccination campaign.”

Biden on Thursday announced a COVID-19 Health Equity Task force to deal with these issues. And internationally, if wealthier countries fail to help countries with less access to the vaccine, Morrison said, “We are at risk of a world in which there are haves and have-nots, and desperate countries may opt for unsafe vaccines … a very mixed and dangerous situation.”

“Viruses don’t care about borders,” Riley added. “One of the biggest lessons learned in this pandemic should be that there has to be some form of solidarity if we are going to avoid another pandemic.”

4) A race against new variants

New COVID-19 variants that have emerged in the United Kingdom and South Africa and begun spreading around the world. Experts believe the U.K. variant is more contagious, and some evidence emerged Friday that it could be more deadly. Riley called the South African variant even more troubling, because it seems resistant to some current treatments for COVID-19.

“In the short term, I am very concerned about the U.K. variant, because until we get people vaccinated, double the transmissibility is very bad news,” Riley said. “In the long term, I am more worried about the South African variant, but I do think we have ways to adjust.”

The new president’s plan, Morrison noted, includes a commitment to boosting genomic surveillance infrastructure. The emerging variants make such initiatives, along with vaccination, all the more urgent.

5) Reasons for optimism

“I think we have the capacity to reach herd immunity and to adjust to variants as they come on,” Riley said, noting that mRNA vaccinations like those made by Pfizer and Moderna might also prove effective against the flu.

“The bottom line is that we are all in this together, and that the only way this will work is if everyone wants it to work,” from Congress providing funding and resources to individuals continuing to wear masks, she said. “If we can do that, I think by the end of the summer, and certainly by fall, things will feel more normal.”

“We are in a terrible period and it’s not over," added Morrison. “We are a very divided country and I am not sure how quickly we can overcome our political pathologies to achieve that kind of behavioral promise,” he said. However, he called the Biden administration’s plan “ambitious, promising, carefully put together and long overdue,” and also praised the scientific research and government investment that led to different and promising vaccines.

“We have a very diverse portfolio [of possible vaccines] that is very promising, from the more conventional to the experimental, and astonishing early results with 94% or 95% efficacy and safety,” he said. “We cannot underestimate what a godsend that is.”

One test, he said, will be where the country stands in October.

“Where will we be in October, as winter returns?” Morrison asked. “If we have achieved durable herd immunity by that point, we will likely escape a return to a winter surge, and that will be a marker of success in my book.”

A PRACTICAL PATH TO DISQUALIFY DONALD TRUMP

The Miller Center's Philip Zelikow says the 14th Amendment is the appropriate tool to deal with the former president's efforts to incite an insurrection

January 22, 2021

Time has come for Congress to contemplate how to hold Donald Trump accountable for his efforts to overthrow the election and incite an insurrection. After all, the last time American citizens made such a concerted, violent effort to overthrow U.S. leaders was in April 1865, when a group of conspirators murdered President Abraham Lincoln and attacked other members of his Cabinet.

As others have noticed, Congress can pursue either impeachment or the invocation of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. Impeachment has gotten the bulk of public attention, but it’s fitting to take a closer look at Section 3. The 14th Amendment path is true to the facts and preferable procedurally, as compared to impeachment.

What America just experienced was an assault by enemies at home who, while claiming to be patriots, sought to override and thus overthrow the Constitution’s procedures for electing a president.

The 14th Amendment disqualifies any enemy of the Constitution of the United States from holding state or federal office if that person, as a public official, had previously taken an oath to support the Constitution. Congress has the duty to enforce the 14th Amendment and only Congress, “by vote of two-thirds of each House[,]” has the power to enforce the provision and to remove the disqualification.

How might Congress go about enforcing Section 3? It can simply decide in any manner it wishes, including a resolution adopted by majority votes, that Donald Trump has “given aid or comfort to the enemies” of the Constitution of the United States. The U.S. Senate, for example, refused to seat Zebulon Vance in 1871 when North Carolina elected him to the Senate because, as a former congressman, he had violated his former oath by serving the Confederacy.

CRITICAL CONDITION

Former Obama administration official Chris Lu, now a Miller Center senior fellow, outlines why federal funds and oversight are vital to Covid-19 vaccine distribution

January 22, 2021

CONTINUING A TROUBLING TREND

Eric Edelman, a former ambassador and Miller Center senior fellow, joins Roger Zakheim in calling for Congress to recommit to civilian control of the military

January 22, 2021

Retired Gen. Lloyd Austin’s nomination to become the nation’s 28th secretary of defense is an important historical milestone marking the first appointment of an African American to the position. Given his accomplishments, and considering that we’re in a moment when white nationalist and racist forces are attacking our democracy, it is easy to see the appeal of a swift confirmation.

That said, his Senate confirmation requires a second, related action from Congress: to waive a long-standing law that prohibits former military officers from serving as secretary unless seven years have passed since their retirement. Both chambers approved a waiver on Thursday, paving the way for his confirmation. This approach leaves the law and our republic’s longstanding principle of civilian control over the military severely wounded.

The principle underlying this prohibition is as old as our republic. Alexander Hamilton devoted attention to the subject multiple times in the Federalist Papers After World War II, Congress saw fit to make the prohibition explicit in the 1947 National Security Act, when it charged the secretary of defense with serving as the principal assistant to the president in all matters related to the management and functioning of the Department of Defense. The rationale for the law is multi-faceted. First, it addressed the Founders’ concern about the dangers that standing armies present the longevity of democratic republics. When Congress created the modern-day Defense Department, the civilian role ensured that intramilitary service rivalries would be managed fairly under an impartial civilian leader.

While echoes of both rationales remain today, the most common justification for the law was captured by Secretary James Mattis, who also had to receive a waiver to serve in the role, during his Senate confirmation hearing in 2017: “Civilian leaders bear these responsibilities because the esprit-de-corps of our military, its can-do spirit, and its obedience to civilian leadership reduces the inclination and power of the military to criticize or oppose the policy it is ultimately ordered to implement.”

The political nature of the position, alone, cuts against the grain of the apolitical ethos embedded in our military.

A ‘HOPEFUL BUT REALISTIC’ INAUGURAL

Chris Lu, a Miller Center senior fellow, joins the Bill Press podcast to review the inauguration of President Biden

January 22, 2021

EXECUTIVE ORDERS AND THE BIDEN ADMINISTRATION'S PLANS FOR GOVERNING

The Miller Center's Barbara Perry joins a panel of experts to explore what the new president's first actions tell us about the path he will take and the obstacles he may encounter for WBUR's On Point

January 21, 2021

FINDING A LOT TO LIKE

Mary Kate Cary, a Miller Center senior fellow and former speechwriter for George H. W. Bush, says conservatives appreciated President Biden's words but will look closely at his actions

January 21, 2021

Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration in 1801 has been on my mind for the last few days. Not only was it the first inaugural address to be delivered in Washington, D.C. and the first to be followed by a parade to the White House, it was the first after a particularly bitter election that ended up going to the House of Representatives.

The inauguration that followed that vote marked the first peaceful transition of power from one party to another, and Jefferson gave one of the greatest inaugural speeches in American history. All eyes were on the new president as he extended an olive branch to his opponent, John Adams: “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.” It turned out Jefferson’s opponents liked the speech better than his supporters did.

I’d bet that like me, most Republicans were relieved.

As a conservative, I was hoping President Joe Biden would do the same in his inaugural address.

I’d bet that like me, most Republicans were relieved when Biden took a pass on getting too partisan. He used the words “unity,” “uniting,” “united” and “union” a total of 15 times in 20 minutes, and referenced the importance of our democracy more than ten times. He gave credit to the heroes who ensured that the attack on the Capitol did not stop our democracy: “It will never happen. Not today, not tomorrow, not ever.”

INSTALLING A CABINET

Melody Barnes, co-director of UVA's Democracy Initiative and a Miller Center professor of practice, tells CNN's Kate Bolduan how the Biden administration will move forward as he builds his government

January 21, 2021

January 21, 2021

WHAT DOES UNITY LOOK LIKE?

Melody Barnes and Laurent Dubois, co-directors of UVA's Democracy Initiative, talk with UVA Today about a key idea in President Biden's Inaugural Address

January 21, 2021

I know that speaking of unity can sound to some like a foolish fantasy. I know that the forces that divide us are deep, and they are real. But I also know that they are not new. Our history has been a constant struggle between the American ideal, that all are created equal, and harsh, ugly reality of racism, classicism, nativism

President Joe Biden

Q. Joe Biden has repeatedly referenced his hope of bringing the country together. What will that actually look like, in your opinion?

Dubois: All of the events of the last few years and the last few months have really made us think about our institutions and Americans’ investment and involvement in the project of democracy itself. As a historian, when I think about what unity might look like now, I think both about the more recent challenges we are dealing with, such as the role social media plays in our politics and our discourse, and then very old issues, questions around race and equality that have essentially been at work since the founding of this country.

We need to find a way to hold, at the same time, our most pressing immediate needs alongside an understanding of the large sweep of our history. Understanding that history, in all its complexity, is the best foundation for unity, and allows us to come together to participate in the future of our democratic institutions, which offer powerful tools for shaping democracy. We will not be united in all of our opinions, of course, but perhaps we can agree on the importance of the tools of democracy in shaping our future.

We need to find a way to hold, at the same time, our most pressing immediate needs alongside an understanding of the large sweep of our history. Understanding that history, in all its complexity, is the best foundation for unity, and allows us to come together to participate in the future of our democratic institutions, which offer powerful tools for shaping democracy. We will not be united in all of our opinions, of course, but perhaps we can agree on the importance of the tools of democracy in shaping our future.

Barnes: I agree, and for many Americans, both those who voted for Biden and those who did not but do accept his presidency, I think unity can come through a spirit of tolerance and pluralism. Joe Biden has already indicated that he wants to reach out to all Americans. I think that will show up in the form of empathy and policy—for the plight of Americans who have lost loved ones to COVID-19, who are suffering because of the pandemic, who are economically insecure in a number of other ways, or who just do not feel like their voices have been heard, especially when it comes to issues of race and ethnicity.

I also think that the way the new president carries himself and approaches his work will be important to many Americans. “Dignity” and “competency” are words that I have heard quite a bit—from progressives and conservatives. Many Americans hope for thoughtful attention to the process of governing, as well as reliance on facts so their circumstances improve.

BIDEN'S THEMES

Barbara Perry, director of Presidential Studies at the Miller Center, explores the president's Inaugural Address

January 21, 2021

OPTIMISM. SHOCK. RESOLVE. GRATITUDE.

William Antholis, the Miller Center's director and CEO, reflects on Inauguration Day

January 20, 2021

Today, Joe Biden will be inaugurated as our 46th president, and Kamala Harris will be sworn in as his vice president.

American inaugurations evoke optimism and reconciliation. That’s been the case since the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing parties, when John Adams yielded to Thomas Jefferson, and Jefferson said, “We are all Republicans. We are all Federalists.”

Even at the moment of our deepest national division—the Secession Crisis of 1860–61—Abraham Lincoln sought to assure the American people. “A disruption of the Federal Union, heretofore only menaced, is now formidably attempted,” Lincoln said. “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.”

Optimism and unity are needed now more than ever. And yet, they will not come easy.

Joe Biden’s inauguration arrives after nearly a year of a pandemic that has cost more than 400,000 American lives. His first steps will be to address the pandemic, and then he will turn to the economic devastation it has wrought—challenges on par with the Civil War and Great Depression.

That’s particularly the case because Biden’s swearing-in comes amid a political crisis, just two weeks to the day after the outgoing president incited a mob to disrupt the counting of votes. In the words of Republican Senate Leader Mitch McConnell: “The mob was fed lies. They were provoked by the president and other powerful people, and they tried to use fear and violence to stop a specific proceeding of the first branch of the federal government which they did not like.” That proceeding was the confirmation of an election that was, by historical standards, not particularly close.

Our nation must grapple with how we got to this point.

The January 6 insurrection threatened the lives of the vice president, members of both chambers of Congress, their staffs, reporters, Capitol police, and hundreds of others. The insurrectionists built gallows just steps away from where Biden and Harris will be sworn in today.

This is a new kind of secessionist crisis, where the president has been encouraging his followers not just to overthrow our democracy, but to secede from reality. Even following the failed insurrection, the president continued to claim a landslide election victory and to tell the roiling mob that he loved them.

Our nation must grapple with how we got to this point.

THE RACE TO CONFIRM CABINET SECRETARIES

Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, a Miller Center senior fellow, looks at a key factor in the Biden administration's potential for early success

January 19, 2021

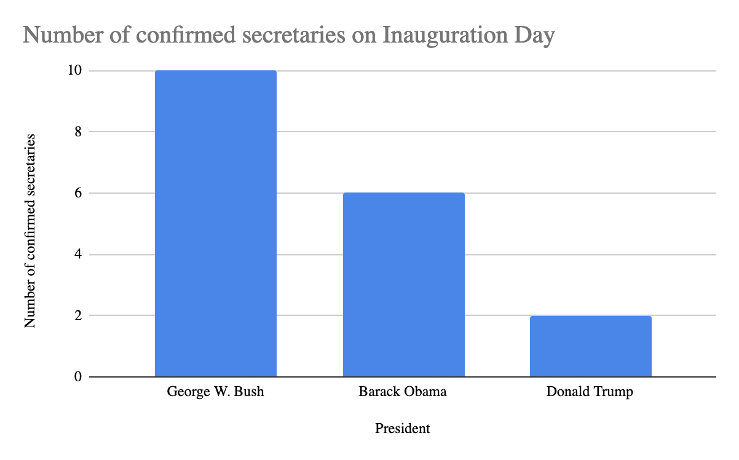

With the Biden inauguration set for tomorrow, January 20, 2021, there is much speculation about whether key cabinet secretaries will be confirmed on that day. After all, since President George W. Bush had ten secretaries confirmed on inauguration day, President Obama had six and President Trump had two, one might expect that a newly inaugurated President Biden might be able to get key cabinet secretaries confirmed.

In addition to confirming cabinet nominees, the Senate must also conduct a second impeachment trial. While it is difficult to forecast the impact of the trial, it is safe to say that it will likely slow down the confirmation process. Looking back at the past three presidents, data indicate that it took President George W. Bush a mere 12 days to secure confirmation for his 14 cabinet secretaries. Interestingly, the time period bumped up to 86 days for President Obama, consuming the first 98 days of his administration to get 14 cabinet secretaries confirmed (note that Defense Secretary Robert Gates held over from the Bush administration). President Trump took just about the same amount of time at 97 days to get 15 cabinet secretaries confirmed.

All three presidents had the advantageous position of their party holding majority control in the Senate. Nevertheless, background checks, financial disclosures, the speed with which nominees submitted their materials, the complexity of personal finances and prior career can lengthen the process. The experience of the past three administrations suggests that despite the relative speed and efficiency that the Biden transition demonstrated in identifying nominees, there are hurdles that will likely delay the confirmation of their carefully picked candidates. Such a delay amidst a pandemic, economic volatility and historically high levels of racial tension is a most unfortunate setback. There is no question that leadership matters and no doubt that the timely processing of nominees should be the Senate’s top priority.

TIMELINE

|

George W. Bush |

Barack Obama |

Donald Trump |

|||

|

Cabinet Secretary |

Date |

Cabinet Secretary |

Date |

Cabinet Secretary |

Date |

|

Agriculture: Veneman |

1/20/01 |

Agriculture:Vilsack |

1/20/09 |

Defense: Mattis |

1/20/17 |

|

Commerce: Evans |

1/20/01 |

Education:Duncan |

1/20/09 |

DHS: Kelly |

1/20/17 |

|

Defense: Rumsfeld |

1/20/01 |

Energy: Chu |

1/20/09 |

Trans: Chao |

1/31/17 |

|

Education: Paige |

1/20/01 |

DHS: Napolitano |

1/20/09 |

State:mTillerson |

2/1/17 |

|

Energy: Abraham |

1/20/01 |

Interior: Salazar |

1/20/09 |

Education: DeVos |

2/7/17 |

|

HHS: Thompson |

1/20/01 |

VA: Shinseki |

1/20/09 |

HHS: Price |

2/10/17 |

|

HUD: Martinez |

1/20/01 |

State: Clinton |

1/21/09 |

Treasury: Mnuchin |

2/13/17 |

|

State: Powell |

1/20/01 |

HUD: Donovan |

1/22/09 |

VA: Shulkin |

2/13/17 |

|

Treasury:O'Neill |

1/20/01 |

Transportation: LaHood |

1/22/09 |

Commerce: Ross |

2/27/17 |

|

Veterans: Principi |

1/20/01 |

Treasury:Geithner |

1/26/09 |

Justice: Sessions |

2/28/17 |

|

Transportation: Mineta |

1/24/01 |

Justice: Holder |

2/2/09 |

Interior: Zinke |

3/1/17 |

|

Labor: Chao |

1/29/01 |

Labor: Solis |

2/24/09 |

Energy: Perry |

3/2/17 |

|

Interior: Norton |

1/30/01 |

Commerce: Locke |

3/24/09 |

HUD: Carson |

3/2/17 |

|

Justice: Ashcroft |

2/1/01 |

HHS: Sebelius |

4/28/09 |

Agriculture: Perdue |

4/24/17 |

|

|

|

|

Labor: Acosta |

4/27/17

|

HISTORIANS ON THE TRUMP LEGACY

The Miller Center's Barbara Perry joins three other historians to examine the Trump presidency as it draws to a close

January 18, 2021

IN A CIVIL WAR, ACCOUNTABILITY MUST PRECEDE HEALING

UVA Democracy Initiative Co-Director Melody Barnes joins UVA historian Caroline Janney in the Washington Post

January 16, 2021

Long before the Trump presidency spiraled completely out of control, many Americans comforted themselves by asserting we were not in a civil war. As we sift through the debris left by the insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol on January 6—and anticipate what is likely to come—we ignore at our peril the cautionary tale of the last Civil War and what followed it.

Today’s reunification efforts, led by Republicans who call for healing just days after the riot, mask challenges much as similar calls did in 1865. Then, as now, we were a country divided by different values, including a contingent willing to use violence and anti-democratic means to accomplish its goals. Healing isn’t possible until those challenges are placed squarely on the table and addressed. Nor is it possible when those who seek to thwart the Constitution aren’t held accountable.

History reminds us that avoiding this difficult work only pushes division and violence into the future.

CAN TRUMP PARDON HIMSELF?

In an event co-hosted by the Miller Center and the Karsh Center for Law and Democracy at the UVA School of Law, legal scholars debate the question

January 15, 2021

This event was made possible thanks to the generous support of the George and Judy Marcus Democracy Praxis Fund.

FIVE QUESTIONS, FIVE ANSWERS ABOUT IMPEACHMENT

Barbara Perry, the Miller Center's director of Presidential Studies, talks with UVA Today about President Trump's historic second trial

January 14, 2021

Q. The House has impeached President Trump for the second time, which has never happened before. Can history tell us anything about how this might go or how we got to this point?

A. Like many things about Donald Trump’s candidacy and presidency, this is unprecedented, and we cannot look to history for a direct example. So there is little to guide us in that respect, but perhaps one signpost, if you will, is what Republican leaders did when President Richard Nixon was investigated during the Watergate scandal in 1974.

After the Supreme Court handed down a unanimous verdict that the president had to turn over tapes of evidence, and the House Judiciary Committee had voted on articles of impeachment, leading members of the Republican Party, including Republican senators and members of Congress, went to the White House and urged Nixon to resign. They reminded him that if he were impeached and convicted, he would lose not only the presidency, but all of the after-office benefits of having been president, and would lose their votes as members of his own party. Ultimately, Nixon did resign before the full House could vote on articles of impeachment.

That example does not offer any legal precedent for us now, but it does offer some historical precedent and also an instructive example of what party leaders did during a difficult time.

Q. The charge, “incitement of insurrection,” is obviously quite serious. What do you make of the House’s choice there?

A. Incitement is defined as promoting, encouraging or provoking illegal activity. To me, it is hard to get much clearer, when you look at Trump’s speech before the riot.

Two constitutional law and First Amendment cases I have read stand out as relevant. In one, Terminiello v. City of Chicago, a man who made a political statement at a rally (criticizing racial and political groups) was convicted of disturbing the peace and was challenging that ruling in the Supreme Court. The court ruled in his favor, but Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote a now-famous dissent arguing that we cannot “convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.” That phrase has resonated with me lately – especially when considering that Jackson had just returned from the Nuremberg trials, where he was the chief U.S. prosecutor.

In another case, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Smith Act of 1940, which made it a criminal offense to advocate for the violent overthrow of the government or to be a member of a group advocating for that. This was created as an anti-communist law, and the chief justice at the time, Frederick M. Vinson, referenced an example from Germany (a failed 1923 coup led by Adolf Hitler known as the Beer Hall Putsch) to argue that we do not have to wait for insurrectionists to be lined up, ready to go and waiting for a signal before the government steps in to prevent an insurrection.

The First Amendment is not absolute; even civil libertarian judges who view themselves as absolutists have drawn the line at speech that leads to conduct. The 1969 Brandenburg v. Ohio case, for example, focused on a KKK rally and established what we now call the “mere advocacy” test, or Brandenburg test. Speech advocating hatred toward a certain group, like Blacks or Jews or Catholics, is protected, that case said, but as soon as you move to advocating conduct, or inciting violence, you lose that protection. Advocating child pornography, for example, is not allowed speech.

So, while a defense could split hairs and say that the president did not literally say, “Go to the Capitol, break in, beat members of the Capitol Police with American flags and fire extinguishers – even killing them – and break and steal …” and everything else we saw, Trump took every step up to that, including giving the signal – “let’s march up to the Capitol and I’m going to be with you.” The only thing he took back was that he didn’t go with them.

Q. How do you expect the Senate trial to unfold?

A. I was surprised to see [Republican] Sen. [Mitch] McConnell express support for impeachment. He does have some leadership authority and could give cover to those who might be afraid of Donald Trump or afraid that they will lose a primary or lose political donations. But I expect most Republican senators, instead of urging Trump to step down like their counterparts in the Nixon era did, will make a political calculation. Is their career, and the office they hold, safer with or without Donald Trump? For [Sens.] Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley, if they are able to maintain their seats, they might determine that it is better to push Trump off the political stage, to pave their own way to the presidency. Other senators might be thinking about how long they have until re-election, or retirement, or what their state is like.

Ultimately, it will take 17 Republican senators to vote for a conviction [which requires a two-thirds vote]. That seems like a high mountain to climb, to me, but things are moving so fast that I wouldn’t put it out of the realm of possibility.

Q. How will this affect President-elect Joe Biden’s first term?

A. This is certainly not ideal, but there is not really anything ideal about how Biden is starting his presidency, from a scaled-back, militarized inauguration to the ongoing pandemic. And, there is precedent for the Senate setting aside half the day for impeachment trials of federal judges, for example, and then proceeding with legislative business for the rest of the day. It can be done.

The timing also raises a question of if it is appropriate to impeach a president after he leaves office. On the one hand, impeachment is intended as a way to get someone out of office, so it seems like a moot point. On the other hand, one of the sanctions on the table is preventing that president from holding office again, and that sanction would still apply even if Trump is no longer in office. We have no precedent to go on, but it seems like having that sanction on the table opens up the possibility of conducting a trial even after a president leaves office.

Q. How might impeachment and/or conviction affect Trump after he leaves office, and if he contemplates another presidential run in 2024?

A. If he is impeached and convicted, I think a sanction will be imposed preventing him from seeking federal office. However, he will almost certainly contest that in court. There has also been some discussion of invoking the third section of the 14th Amendment, which was meant for Confederates and bans people who engage in rebellion or sedition from holding public office. A reference to that amendment is including in the impeachment articles, I think to give weight to the “incitement of insurrection” charge, but it’s unclear if it can be applied without a conviction in a civil court of law, for example, or without additional legislation spelling out what that means. Many very smart constitutional law scholars have differing opinions on how exactly that amendment would be applied.

Beyond the courts, I believe that Trump will use all of this to refashion himself as this great hero of the kinds of people who engaged in that violent insurrection on Jan. 6., and to continue to gin up the anger he has been ginning up since 2016, and before that with the birther movement. To me, a key question is how the Republican Party will react to that, and if Trump voters—not just far-right-wing or militia types—but a broad base of voters will continue following him, even when he does not have presidential power. I think the answer is yes, but we don’t know yet.

LISTEN: JOE BIDEN'S FIRST 100 DAYS

Barbara Perry, the Miller Center's director of Presidential Studies, joins other experts on Barrons live

January 13, 2021

A BLUEPRINT FOR BIDEN

Steven M. Gillon, a Miller Center senior fellow, says the new president and the GOP's Mitt Romney can learn from President Clinton

January 13, 2021

Our system enshrines Jan. 6 as the day when members of Congress gather and perform the ceremonial function of counting the previously certified votes of the electoral college and announcing the winner of the presidential election — a shining model for fledgling democracies everywhere.

Instead, on Wednesday the world witnessed an attempted insurrection by an angry mob that stormed and sacked the Capitol, threatened the lives of the nation’s elected officials, killed a Capitol police officer and disrespected our democratic norms.

The implications are grave. The mob was motivated by lies — lies perpetuated by the conservative media ecosystem, by self-serving politicians like Sens. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) and Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), and most of all by the egotistical demagogue in the White House who has incessantly refused to accept the results of the most transparent election in American history.

These lies will continue to fester unless our elected leaders, both Democratic and Republican, break the pattern that has crippled our politics for far longer than four years.

It is tempting to cynically assume that they won’t. Best case, President-elect Joe Biden will assume power and Republicans will pick up where they left off when Barack Obama occupied the White House, pursuing a scorched-earth policy of resisting the president at every turn.

But historically, crises produce moments of great opportunity. And millions of Americans who watched the horrifying images on television are looking for elected leaders to offer plausible explanations and constructive solutions.

In April 1995, Americans experienced a similar moment when white power and anti-government terrorists Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols detonated 4,800 pounds of explosives in front of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people, including 19 children. How President Bill Clinton and House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) responded to the tragedy during a moment of intense partisan division offers a lesson for redirecting our politics today.

MOVING FORWARD

Chris Lu, a Miller Center senior fellow, a member of the Biden transition team who also led the Obama transition, assesses how the new president may respond to the events of January 6

January 13, 2021

ASSESSING THE DIVERSITY IN THE BIDEN ADMINISTRATION

President-elect Biden has more officials to name, but Miller Center senior fellow Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, says we have enough to consider its composition

January 13, 2021

Despite the truncated transition brought on by President Trump’s refusal to concede the election and Emily Murphy, administrator of the General Services Administration, also refusing to certify the transition for nearly three weeks—the delay has not affected the pace of President-elect Biden’s appointments. In fact, the Biden transition is well ahead of his seven predecessors. As of Jan. 7, the transition had publicly identified the top 15 Cabinet members. The completion of these highly visible appointments provides the opportunity to compare the relative diversity (in terms of race/ethnicity, gender, and age) of the Biden Cabinet to his six predecessors at the start of their administrations.

The importance of this exercise is highlighted by the president-elect’s pledge to create a Cabinet that looked like America. President-elect Biden stated, “I’m going to keep my commitment that the administration, both in the White House and outside in the Cabinet, is going to look like the country.” In addition, the pivotal role of Black voters in the South Carolina primary as well as the critical Georgia presidential and Senate races, has drawn a great deal of attention to President-elect Biden’s selection of Black appointees. Of course, there are numerous influential appointments across the executive branch and within the White House Office that remain. These 15 appointments are merely a highly visible subset of the nearly 1,200 Senate-confirmed positions that will be filled over the course of the Biden administration.

Although President-elect Biden expressed his desire to appoint a diverse Cabinet, the comparison to his six predecessors shows that he tied with President Obama in terms of non-white appointments, while President Clinton exceeded both on a percentage basis.

WHAT ARE WE TO THINK?

UVA experts react to the assault on the U.S. Capitol

January 11, 2021

On January 6, the head of the executive branch of the United States government, President Donald Trump, suggested his followers proceed to the home of the legislative branch to protest the validation of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. What followed shocked much of the American public, even in an era of tottering democratic norms. And one can only imagine what would have happened had a U.S. Senator sent a similar mob to breach the walls of the White House or ransack the Supreme Court.

In the aftermath, UVA experts offered their perspective.

“Work to find justice”

Barbara Perry visited CNBC's SquawkBox Europe:

“There can be no reconciliation without truth.”

Melody Barnes is co-director of UVA's Democracy Initiative and a professor of practice at the Miller Center. She joined CBC's American Roundtable panel on Rosemary Barton Live:

“Seditious conspiracy”

Miller Center senior fellow Eric Edelman served as a U.S. diplomat for three decades, including stints as U.S ambassador to Turkey and to Finland. He joined other guests on Mona Charen's podcast, Beg to Differ:

“A serious test of our most basic political institutions”

Micah Schwartzman is the director of the Karsh Center for Law and Democracy and the Joseph W. Dorn Research Professor of Law. He joined UVA Today to answer the questions, "Was the Attack on the Capitol a ‘Coup’?" and "What Happens Now?"

Q. What do you think the events mean for how we think of our democratic institutions?

A. The attack on the U.S. Capitol was a disgrace to our democracy and a serious test of our most basic political institutions. How Congress responds between now and the inauguration of President Joseph Biden and Vice-President Kamala Harris Jan. 20 will be long remembered.

Q. What impact could this have globally on our reputation as a democracy?

A. American democratic institutions have suffered years of degradation, but what happened on Jan. 6 was shocking, both here and around the world. The next administration, along with the other branches of government, must begin what is certain to be a long process of rebuilding our reputation as a leader among democratic nations.

Q. What lessons can we learn from what has happened? What missteps can we avoid?

A. We have to learn to take seriously threats to fundamental institutions, principles and norms. We can’t ignore those threats, or appease those who make them, because they might seem absurd, ludicrous, fringe, joking or too shallow or bumbling to pose any real risk.

Political violence doesn’t happen all at once. It emerges from a process of degrading and breaking down trust in our democratic systems, including fair and open elections, and we have to be vigilant about protecting them.

Q. What steps can we take to repair the damage?

A. After many years of corruption and damage to our democracy, there is a lot of rebuilding to do, starting with protecting and expanding voting rights, restoring faith in the integrity of our democratic process and shoring up the rule of law. We need a president and a Congress that clearly, unmistakably and forcefully reject white supremacy, which was on display at the Capitol building on Jan. 6 as much as it was in Charlottesville on August of 2017. Our nation’s struggle with racism is far from over, and we have to say that out loud. We also need to reduce the massive economic inequalities that have contributed to declining social and political trust, especially in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Q. Soon-to-be Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, House Speaker Leader Nancy Pelosi and many others are calling for Trump to be removed from office. What are the realistic legal options for that?

A. There are two options being discussed right now: impeachment and invoking the 25th Amendment, in which Trump’s Cabinet, led by Pence, would have to determine the president is unfit to hold office. (Trump’s term expires on Jan. 20, the day Biden will be sworn in.)

There are timing problems with both these approaches, and the vice president seems to have signaled some reluctance to pursue the latter. But there appears to be bipartisan support for removing the president, and it’s possible we could see articles of impeachment drawn up in the House of Representatives.

Q. How far does the First Amendment go to protect Trump’s incitement to riot?

A. The First Amendment provides strong protections for political speech, but under the Supreme Court’s famous test from Brandenburg v. Ohio, speech is not protected if it “is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Members of Congress, including senators from both parties, have accused the president of doing just that—inciting a mob of armed supporters, who then proceeded to sack the U.S. Capitol building.

Q. In legal terms, do you view what happened Jan. 6 as a coup? Something else?

A. I wouldn’t describe the violent mob attack on the Capitol as a “coup,” although it might have been part of an attempt at one. I think a coup requires more systematic seizure of power, usually by the military or by paramilitary groups.

But the rioters who stormed the Capitol might have thought they were trying to overthrow the government, and they succeeded in temporarily disrupting a critical part of our democratic process, which was the counting of electoral votes.

Some officials have called what happened an “insurrection” and a “seditious conspiracy,” both of which are punishable under federal law. Those seem like better descriptions to me.

‘THEY'VE LEFT THE PARTY IN ABSOLUTE TATTERS’

Miller Center senior fellow Mary Kate Cary joins CTV to assess the events of January 6

January 7, 2021

AMERICAN ADVOCATES FOR GLOBAL DEMOCRACY MUST NOW LOOK CLOSER TO HOME

Miller Center senior fellow Aynne Kokas on the disturbing invasion of the U.S. Capitol

January 7, 2021

On January 6th, the U.S. Capitol police dispersed violent extremists who stormed the U.S. Capitol. Armed throngs invaded Congress’s hallowed halls to undermine the peaceful transfer of power via the certification of the electoral college. The U.S. Capitol is only one part of the U.S. Capitol complex. The Capitol Police also evacuated buildings around the Capitol, including the Library of Congress, where I was a fellow at the Kluge Center before the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown. As a scholar of U.S.-China relations, what strikes me most is that while lawmakers condemn anti-democratic actions abroad, we fail our core institutions, those that seek to build a timeless democracy through knowledge.

It is clear that we were wrong to take for granted the possibility of long-term stability amidst short-term chaos.

When I was in residence at the Library, the tunnels connecting the Capitol building and the marble-hewn collections felt like a ballast for the then metaphorically violent ideological explosions in Congress. Hill staffer friends would come across to the Library for coffee to remember what the timelessness of democracy felt like. With actual violence descending onto Capitol Hill, as I sit in my home under curfew nearby, it is clear that we were wrong to take for granted the possibility of long-term stability amidst short-term chaos.

Republican lawmakers have long been staunch supporters of the democracy movement in Hong Kong, arguing for the sanctity of the democracy movement. Senator Josh Hawley, a leading figure in the efforts to decertify the electoral college votes, introduced a resolution in May condemning Hong Kong’s anti-democratic national security law. Ted Cruz spoke at a Senate judiciary sub-committee meeting in support of pro-democracy Hong Kong activists in December. Yet both Senators fomented anti-democratic efforts to block the certification of legal electoral college results. On January 6th, Republican lawmakers condemned Hong Kong police officers arrested 53 democracy protesters under the Special Administrative Region’s national security law for their participation in and organization of primaries for the Hong Kong Legislative Council elections.

THE EXTRAORDINARY LETTER

Miller Center senior fellow Eric Edelman explains why and how ten former secretaries of defense wrote a letter urging U.S. military leaders to resist any calls to intervene in electoral disputes

January 5, 2021

In an extraordinary time it was an extraordinary letter. Ten former civilian heads of the United States military felt compelled to assert that "efforts to involve the U.S. armed forces in resolving election disputes would take us into dangerous, unlawful and unconstitutional territory.

"Our elections have occurred. Recounts and audits have been conducted. Appropriate challenges have been addressed by the courts. Governors have certified the results. And the electoral college has voted. The time for questioning the results has passed; the time for the formal counting of the electoral college votes, as prescribed in the Constitution and statute, has arrived."

How did the effort come together, and perhaps even more importantly, what led them to state was has long been accepted in the United States of America? Eric Edelman, a longtime U.S. diplomat, now a Miller Center senior fellow, was a key player. He tells Charlie Sykes how it happened.

TRUMP'S ‘SMOKING GUN’ TAPE IS WORSE THAN NIXON'S

But Repubicans have less incentive to do anything about it, writes Miller Center Nixon scholar Ken Hughes

January 5, 2021

At least Donald Trump’s “smoking gun” tape is simpler than Richard Nixon’s.

Schoolchildren can easily grasp Trump’s high crime, in contrast to the complex, Machiavellian plot immortalized on the tape that led to Nixon’s downfall. It will be harder to explain to them why congressional Republicans decided to hold Nixon accountable, but not Trump.

It certainly wasn’t for lack of evidence. The tape is clear. Children can identify the principle at stake. They understand cheating. They know that the loser of a race should not declare himself the winner. They know it’s wrong for the loser to try to change the results of the race by threatening those who keep the score and enforce the rules.

Presidential coercion

That is what Trump, the loser of the 2020 election, tried to do to the top election official in Georgia, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, in a phone call on Saturday.

“I just want to find 11,780 votes,” Trump said.

Trump lost Georgia by 11,779 votes. To pressure this state official to do his bidding, Trump brandished the threat of criminal prosecution. He claimed—falsely, baselessly and ridiculously—that Georgia’s ballots were corrupt even as he was trying to corrupt them himself:

You are going to find that they are—which is totally illegal—it is more illegal for you than it is for them because, you know, what they did and you’re not reporting it. That’s a criminal, that’s a criminal offense. And you can’t let that happen. That’s a big risk to you and to Ryan [Germany], your lawyer.

The nature of this threat (nice place you got here, hate to see anything happen to it … or to you) won’t be lost on anyone familiar with mobster movies. Trump’s take on the tough-guy cliché wasn’t particularly coherent, but it met the trope’s two basic requirements. It was both clear enough to be unmistakable, and vague enough to minimize his own exposure to criminal prosecution.

PRESIDENTIAL TRANSITIONS DIDN'T USE TO MATTER

Here's why they matter now, says the Miller Center's Russell Riley

January 5, 2021

Presidential transitions have become major productions. The moment the General Services Administration ascertained that Joe Biden was the winner of the 2020 election, he received $6.3 million in federal money for transitional staff and the keys to a 175,000-square-foot office building just blocks from the White House to headquarter them. A cottage industry of experts on proper transitioning technique has emerged to provide guidance to newcomers on everything from White House organization to surviving background checks. And the pages of the nation’s newspapers have for weeks tracked in detail the president-elect’s personnel decisions, often drawing conclusions from tea leaves about the kind of presidency the nation is bound to experience over the next four years.

But it was not always so. Indeed the term “presidential transition” was not even in general circulation until at least 1948.

On Oct. 19 of that year, in an unsigned editorial, The Washington Post took to task Republican presidential nominee Thomas Dewey for saying that if he defeated the incumbent Harry S. Truman, he intended to begin work immediately reshaping American foreign policy while holding onto his day job as New York’s governor until the inauguration. The Post thought it inadvisable that the president-elect of the world’s most powerful nation would allow himself to be “burdened with questions as to how much shall be spent for roads, schools, and hospitals” in the Empire State. Truman, of course, made that a moot point when he won the election weeks later.

The term “presidential transition” was not even in general circulation until at least 1948.

That otherwise inconspicuous article is historically significant, however, because electronic databases indicate that it is the first time the phrase “presidential transition” appears in print in a major American newspaper. This is at once surprising and instructive. Given today’s breathless coverage of virtually every detail of the Biden transition, it is hard to imagine a time when such developments were not followed obsessively. But that reality illuminates something important about the changing role of the presidency in our political system.

Americans had almost 150 years of experience in baton-passing from one president to the next at the time this article appeared. Yet what we now know as the presidential transition was insufficiently distinctive in that interval to merit a special term of art. It was literally unremarkable.

"THAT'S NOT THE WAY IT WORKS IN OUR COUNTRY"

Miller Center senior fellow Chris Lu, who ran the Obama administration's transition, assesses efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election

January 3, 2021

PRESIDENTIAL TRANSITIONS WERE NOT ALWAYS A THING

Co-chair of the Miller Center's Presidential Oral History Program, Russell Riley writes about how the transfer of power from one incumbent to the next wasn't always fraught with risk

December 18, 2020

Given the current obsession with the transition from Donald Trump to Joe Biden, it is striking that for most of American history, presidential transitions were not really a thing. The president’s job responsibilities before the New Deal and World War II were comparatively modest, and thus, the transfer of power from one incumbent to the next was not commonly fraught with genuine risk and thus unworthy of special attention.

Too, before 1933, presidential inaugurals occurred on March 4, rather than late January. That gave incoming administrations four months to prepare for a measured and nondescript slide into the White House. It was a combination of the bombing of Hiroshima and the 20th Amendment that propelled into existence the concept of the “presidential transition.”

THE WORLD BIDEN'S NATIONAL SECURITY TEAM WILL INHERIT

Miller Center senior fellow Eric Edelman assesses the challenges of strategic competition with Russia and China, emergent nuclear threats, and Islamist extremism

December 16, 2020

The initial statements and early national security appointments of President-elect Joe Biden should help lay to rest any lingering fears from the recent presidential campaign that he was suffering from low-grade dementia and that he would easily become a tool of the Democratic Party’s left wing. Perhaps the best proof of this is the fact that squeals of rage and protest that are emanating from both the “progressive” left and right-wing non-interventionists of the Koch-Soros-funded school of “restrained” (read isolationist) foreign policy for the United States, as well as the frantic campaign they seem to have waged successfully to block the candidacy of well-known centrist Michele Flournoy for secretary of defense. Still, every new administration, especially one that was recently in power, has to take stock of how the world has changed and contend with a shake-down cruise on national security issues in its first year. In that context, how is the new Biden team shaping up, and what kinds of challenges is it likely to face?

Every new administration, especially one that was recently in power, has to take stock of how the world has changed.

The Team

One strength of the incoming administration is that Biden has not put together a “team of rivals” but rather a team of colleagues with strong pre-existing relationships with the president-elect and with one another. That could insulate them against the bureaucratic infighting that has all too often prevented coherent policymaking in both Democratic and Republican administrations since the 1970s. Although there is always a danger that such a team will fall victim to “groupthink,” naming Jake Sullivan—who is known for playing devil’s advocate and ruthlessly questioning assumptions—to the national security adviser’s role may help mitigate that risk.

The team that Biden has announced stands pretty squarely in the moderate tradition of liberal internationalism that animated the post-Cold War administrations of Bill Clinton and, to a lesser extent, Barack Obama. The team shares a belief in the importance of U.S. global leadership (with varying degrees of skepticism about how easy this will be to reassert in the wake of Donald Trump), a commitment to the value of U.S. alliances and partnerships around the world (with some advocating more or less “tough love” for some allies), a conviction that the U.S. is facing greater competition from a variety of authoritarian actors in the international arena, and a creedal commitment to multilateral diplomacy as a major tool to advance U.S. interests around the world.

THE PRESIDENT-ELECT AND THE ‘NEW SECESSIONISTS’

Uniting a pro-reality supermajority

December 15, 2020

Now that the Electoral College has cast its votes, President-elect Biden faces a new secession crisis.

Unlike the one faced by Abraham Lincoln during his transition in 1860 and 1861, this one will not lead to civil war. But Joe Biden still must address it—first by uniting the supermajority of Americans who are committed to a united state of reality.

Lincoln’s crisis featured the secession of seven states. In December 1860, six weeks after Lincoln’s victory, South Carolina became the first state to secede. Over the next two months, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas would follow suit. The secessionists feared Lincoln would immediately and directly dismantle the slave economy. Newspapers—operating at warp speed, thanks to the day’s breakthrough communications technology of the telegraph—helped fuel an alternative reality.

Biden’s crisis is not about states, but about state of mind. About two-thirds of the country believe that Biden won the election, fair and square. But another one-third does not. One poll identified about 36 percent of voters believe Biden’s victory was due to fraud—or 77 percent of the 47 percent who voted for his opponent. An equal number are “angry at the idea that Biden won.” In a different poll, 73 percent of respondents said Biden won, with less than one-third of voters thinking the election was “rigged.”

Biden’s crisis is not about states, but about state of mind.

The failed Supreme Court pleading, supported by 19 state attorneys general and 126 members of Congress, is the clearest demonstration that today’s secessionists are withdrawing from truth. The suit denied the reality of Republican officials in battleground states who have certified the election. It ignores the Republican-appointed judges and the nation’s attorney general, who have rejected fraud and election-rigging charges for lack of evidence. It ignores reliably conservative news outlets such as FOX News and the Wall Street Journal, and personalities as Tucker Carlson, Karl Rove, Erick Erickson, and Andy McCarthy, who have warned that overturning the votes of millions of Americans may forever undermine our elections.

The New Secessionists are not necessarily bigots or racists. As a whole, they are not yet violent. But threats of violence against election officials—from Michigan to Georgia, Pennsylvania to Arizona—are rising.

The New Secessionists’ undoing goes deeper than the election. As Jonathan Rauch, David Brooks, and Peter Wehner have pointed out, the New Secessionists reject the institutions responsible for policing facts: our government and courts, our media, academia, and science. To be sure, these imperfect institutions are subject to human error. But the New Secessionists ignore our institutions’ most redeeming features: openness to review, to reform, and to reality itself.

Threats of violence against election officials are rising.

The secessionists are beginning to create a new imagined nation within our nation. The political scientist, Benedict Anderson, famously defined a nation as “an imagined community.” Anderson showed how the spread of newspapers in the late 1700s helped to forge national identities—often in colonies that then seceded from their mother nations. The New Secessionists are elevating media platforms like Newsmax, OAN, the Epoch Times, and Parler to forge an imagination-fueled society.

How should Biden react? Lincoln provides an example. In February 1861, the president-elect’s train sped a mile a minute from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington, D.C., but he did not choose a direct path. As historian Ted Widmer describes it in Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington, his route zig-zagged through Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and western Pennsylvania, up and across New York, down the Hudson River to New York City and then to New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, and Maryland—symbolically trying to unite a disparate collection of states and peoples. His inaugural address pleaded to the South for peace and reconciliation, arguing that we must be friends, not enemies.

President-elect Biden already has embraced Lincoln’s model. Biden has said repeatedly: “I’ll be a president for all Americans. Not just the ones who vote for me.”

His first priority should be to unite the two-thirds of the nation who still live in the current reality. More than 51 percent of voters, or about 81 million Americans, chose Biden. Another roughly 20 million did not vote for Biden but accept that he won. Serving those 100 million voters must be Biden’s first tour of duty.

How to unite reality-based America? Biden’s base is made up of center-Left voters. His challenge will be how to maintain the civic loyalty—and the patriotism—of both Bernie Sanders Democrats and Doug Ducey Republicans. Sanders and his followers want systemic change. Doug Ducey, Arizona’s Republican governor, accepted Biden’s victory but voted against him because he feared Sanders-style socialism.

Fortunately, each of the nation’s other crises present opportunities for uniting reality-based supermajorities. The coronavirus pandemic is most obvious. In an October poll, three-quarters of Americans support common-sense actions to mitigate the further spread of Covid-19, to treat the ill, and to vaccinate the healthy.

Economic revitalization is step two. While it is certainly the case that Democratic socialists and reality-based Republicans have different economic priorities, there is strong political support for at least one more large emergency package, and perhaps for another one to follow. The second bill will likely focus on infrastructure investments and perhaps also support industries that may take time to recover: airlines, hotels, restaurants, etc.

Biden also prioritized racial justice and climate change during his campaign. These are higher priorities for his supporters than they are for Republicans. Still, he can still find allies across the aisle dedicated to ending discrimination and to lowering emissions and producing clean energy.

The nation’s other crises present opportunities for uniting reality-based supermajorities.

As important, Biden already has applauded Democratic, Republican, and Independent election officials and politicians who courageously secured fair elections in Georgia, Arizona, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. The Republican officials may not want a new Democratic president’s endorsement. But Biden must at least hear their hopes and fears.

What about the one-third of the country who are the New Secessionists? Lincoln treated secessionists in his era as friends not enemies. President-elect Biden cannot accept their reality, nor should he. But if they meaningfully want to engage on further strengthening our election systems, the president-elect should engage. If they want to address bias in the media, universities, and other reality-based institutions, he should be open to those discussions. That said, review and action must be tethered to a reality that can be fully acknowledged and accepted by the other two-thirds of the nation. That must be nonnegotiable.

—William Antholis, director and CEO, Miller Center

THE STATE OF THE TRANSITION

Miller Center senior fellow Kathryn Dunn Tenpas assesses the progress of the Biden transition on The Current, a podcast from the Brookings Institution

December 14, 2020

BIDEN TURNS TO OBAMA STALWARTS FOR CABINET

On NPR's All Things Considered, Kathryn Dunn Tenpas talks about the challenges for advisors from previous administrations

December 11, 2020

Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, who has studied administrations back to President Reagan and is a practitioner senior fellow with the Miller Center, says that the best source of employees is from previous administrations because they know the ropes. She also says that Biden's inner circle is coming back to a completely different situation than their first go-around.

"What is the status quo?" she asked. "We are certainly not in an era right now where it's status quo. We have a pandemic on our hands. The economy is faltering. We have really high racial tension in our country. I don't think it was like that in 2009."

Listen to the full conversation:

BIDEN AND THE PROGRESSIVE LEFT

The Miller Center's Guian McKee writes how LBJ demonstrated what not to do when dealing with a splintered Democratic Party

December 11, 2020

Among the many problems that will face Joe Biden when he takes office on January 20 is the question of how to manage his administration’s relationship with the progressive wing of his own party. Although Biden actually moved significantly to the left on key issues over the primary and general election, progressives are already pushing the new administration to adopt its priorities in areas from health care to climate change to racial justice. On November 19, for example, Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez and other members of “The Squad” led a demonstration outside Democratic National Committee headquarters to demand that the new administration act rapidly on the climate crisis.

Such efforts are certain to intensify once Biden is sworn in as president. Handling such intra-party tensions will be crucial to his ability to keep Democrats unified in the face of what is likely to be intransigent Republican opposition to anything the new administration does.

Biden is far from the first president to face ideological tensions within his own party. One case stands out, though, in part because a secret White House taping system captured key aspects of the resulting conflict: that of Lyndon Johnson in the aftermath of his landslide 1964 election victory.

LBJ provides a negative model: what Biden should not do in response to the new progressives of the 2020s.

With large Democratic majorities in the new Congress, LBJ succeeded in passing landmark legislation on voting rights, health care, education, anti-poverty, housing, environmental protection, and the arts—the full range of what the administration had dubbed “the Great Society.”

Yet all was not well. Protests against the war in Vietnam and rebellions against racial injustice in American cities grew larger and more divisive. By mid-1966, Johnson’s critics challenged not only his continuation of the war, but also what they saw as an inadequate response to poverty and racial discrimination at home.

Among those calling for a greatly expanded federal effort in the latter area was Johnson’s bitter rival, Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York, who had begun to fashion an urban anti-poverty program based on new ideas about direct public and private investment in community-based economic development. Meanwhile, Kennedy privately derided Johnson’s proposed Demonstration Cities bill (later known as “Model Cities”): “It’s too little, it’s nothing, we have to do 20 times as much.”

On August 1, 1966, the insurgency emerged in Congress when Senator Abraham Ribicoff of Connecticut (formerly Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare under President Kennedy) announced that he would soon hold a series of hearings on the problems of American cities in the Senate Government Operations Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization, which he chaired. Kennedy also served on the committee, and Johnson saw the hand of the slain president’s brother at work in the pending Ribicoff hearings. The next day, he explained this in a recorded phone call to Treasury Secretary Joe Fowler:

President Johnson: What I’m more concerned about than anything else now is that [Robert F.] Bobby Kennedy [D–New York], Martin Luther King [Jr.], that [Joseph W.] Joe Alsop, all the papers, New York Times—they’re getting on a hundred-billion-dollar jag for the cities.

Fowler: Yeah.

President Johnson: And I’ve got a 2-billion-dollar bill that they won’t pass, but they want a hundred billion. And that’s 10 billion [dollars] a year for 10 years. Now, if we got anything like that, we’d really be ruined. And I think that’s what they’re going to do with these riots. And I think they’re going to have enough riots going on. I think, just between us, that Bobby’s busy riding the labor people and riding the Negros so that he can provide the solution. [Snorts.]

Johnson had thus concluded that Kennedy would take advantage of urban unrest, and possibly even tacitly encourage it, in order to further his own policy and political goals. In an August 10 conversation with Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield of Montana, Johnson warned that the hearings would jeopardize moderate and conservative Democrats around the country:

You know we’re going to destroy ourselves with this interparty politicking, don’t you?

President Johnson: Now, Mike, you know we’re going to destroy ourselves with this interparty politicking, don’t you?

Mansfield: Yes, sir.

---

President Johnson: And I think that you and Dirksen ought to sit down and talk to [John L.] McClellan [D–Arkansas] and the ranking member of Government Operations. And this committee has no jurisdiction in the world to report a damn thing. It—All it’s going to do is stir it up. It’s an oversight committee.

Mansfield: Yeah.

President Johnson: And I think that if you’ve got to stir up something, you ought to do it in January, because you’re just going to beat the hell out of people like [Lee W.] Metcalf [D–Montana] and these boys in Omaha, Nebraska, that are in Congress, and five from Iowa, with all this damn fool $100 billion Negro stuff.

Mansfield: Yeah.

President Johnson: They just cannot survive in those little rural states. And Bobby’s elected, but he ran a million and half behind me in New York. And they just—you see what happened in Arkansas yesterday.

Mansfield: Yeah.

...He was sitting on a tinder box. He’s got 100,000 Negroes, and the Poles, and the Germans, and everything are fighting each other. And we’re stirring it up, up there

President Johnson: And I don’t think we can stand this publicity. I think that [Chicago Mayor Richard J. “Dick”] Daley’s called me half a dozen times, and he said if you don’t stop Bobby and them here it’s just going to ruin me. He’s got all the Poles mad, and got all the Germans mad, got all the Italians mad, and [Mayor Henry W.] Maier from Milwaukee was in this morning, said he was sitting on a tinder box. He’s got 100,000 Negroes, and the Poles, and the Germans, and everything are fighting each other. And we’re stirring it up, up there, and Teddy [Kennedy] went down to Jackson, Mississippi, and said, “If you can spend 2 billion [dollars] on the soldiers in Vietnam, you ought to spend 2 billion [dollars] on the Negroes.” And [it is] the shearest demagoguery, saying that “if you can spend 24 billion [dollars] a year on 16 million Vietnamese, 14 million, [then] you can spend that much on 20 million good Negro Americans.” Well—

Mansfield: [faintly] That’s terrible.

Johnson had clearly concluded that his interests lay with the center of his party, and in limiting a possible backlash from racially-conservative ethnic whites. As such, he saw little value in working with the party’s left, much less with even more radical figures in the Civil Rights movement. The next day, he expounded on that point in a conversation with Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach:

President Johnson: I’m afraid that it’s going to stir up these things out here in the countryside—the Stokely Carmichaels and so forth—to such an extent that we really get them antagonized. Now, what I’ve got is I’ve got the people just calling me every day on this civil rights thing and I think if we don’t get it through pretty quick, we’re not going to get many of them because they’re sure getting mad.

Katzenbach: Yes, I know they are.

President Johnson: [Daniel D. “Dan”] Rostenkowski [D–Illinois] called last night and was rather abusive because I hadn’t denounced the rioters or nullified, and they quoted him what I said in Indianapolis. [Roman C.] Pucinski’s [D–Illinois] written a big a letter to us. And I was talking to some of the boys from the northern areas, upstate New York and others, and they’re bitter. The Buffaloes and others.

Katzenbach: No, they are. There’s no question.

President Johnson: And I think we better—our whole future may not be with just Stokely Carmichael.

Katzenbach: No, I agree with that.

Although many of the witnesses at the hearings proved highly critical of Johnson’s anti-poverty efforts and called for a massive increase in federal and private support for development in the cities, neither Kennedy nor Ribicoff directly endorsed the level of expenditures that Johnson feared. Nonetheless, the hearings set out a liberal marker for a more aggressive approach than the President was willing to contemplate. In November’s midterm elections, the Democrats lost forty-seven seats in the House and three in the Senate, vastly reducing their majorities and limiting Johnson’s room to maneuver. By the end of the year, the fight over funding had turned back to the War on Poverty. Office of Economic Opportunity Director Sargent Shriver pushed for more funds for his agency, and contemplated resigning if Johnson and Congress did not agree. On the day after Christmas, LBJ discussed the situation with Press Secretary Bill Moyers:

I think that’s hurt poverty more than anything in the world is that these Commies are parading, and these kids, long-hairs, saying, you know, that they want poverty instead of Vietnam, and the Negroes. And I think that’s what the people regard as the Great Society

President Johnson: Now, I’m not anxious for him [Shriver] to stay, more than I am Bundy. I would like for him to, and I think he’s the best one for it. And he has my support and my confidence, and so forth. And I will, whatever figure I give in the budget, I will fight for it, as I did last year. But I cannot keep him from being the victim of Bobby [Kennedy] and [Abraham A. “Abe”] Ribicoff [D–Connecticut] and [Joseph S.] Joe Clark [Jr.] [D–Pennsylvania] and [Wayne L.] Morse [D–Oregon]. And I cannot keep him from being victim to the Commies who were out here yesterday and said, “Give the money to poverty, not Vietnam.” And I think that’s hurt poverty more than anything in the world is that these Commies are parading, and these kids, long-hairs, saying, you know, that they want poverty instead of Vietnam, and the Negroes. And I think that’s what the people regard as the Great Society.

So you look into that and call the signal; make the decision. And if he comes, maybe you come with him, or if you don’t want to be involved in that kind of discussion, suggest to him what the agenda is, what we [will] talk about.

Moyers: All right.

President Johnson: I do not want to debate the budget now, because I’m going to send up my budget late. And I cannot tell till I make the tax decisions how far I dare go. And I think . . . I don’t think he knows this and I don’t think he thinks this—[Henry H. “Joe”] Fowler’s calling me now—but, in my judgment, the bigger request I make for poverty, the more danger it is of being killed. I don’t think they’re just going to cut it. I don’t think—I think the same thing about [foreign] aid. I think if I ask for 2 billion or 3 billion [dollars] for poverty, when I got 3 billion jobs, and I’m spending 24 billion in other fields, I think they’d say, “Good God, it goes up every time he gets somebody a job; it costs you more.” I think if we increase it a reasonable amount, that we have a much better chance of fighting and holding it.

Johnson’s linkage here of his liberal opponents in the Senate to what he saw as the “commies” and “long-hairs” protesting in the streets is telling. By this point in his presidency, LBJ had let himself become boxed in not only by Vietnam and its resulting budgetary pressures, but by his own anger at his opponents on the left and his resentment at their failure to appreciate how much he had already accomplished on Civil Rights and through his anti-poverty efforts.

This is the negative model that Joe Biden must avoid in the difficult and controversial moments that are sure to emerge in the coming years between his administration and the modern progressive left. Anger at under-appreciation, or frustration at the left’s unwillingness to acknowledge the constraints that Biden may believe he faces, are both natural and human reactions. LBJ let these emotions overwhelm him.

Possessed of a very different personality, Biden should be better able to resist such destructive temptations. In his 2012 victory speech, President Obama referred to his vice president as “America’s Happy Warrior.” The phrase originates in a poem by William Wordsworth, and has previously been used to describe political figures as varied as Grover Cleveland (who applied it to himself), Al Smith, Hubert Humphrey, and Ted Kennedy (also by Obama). Biden would do well to maintain such a persona as a positive model in dealing with the left, in contrast to LBJ’s self-destructive rants, regardless of what the next four years may bring. For one, it will serve him well with less ideological elements of the American electorate, who will be crucial to his success. For another, it will help him remain open to real opportunities that progressives may recognize, and to the new ideas that the left brings to the table for addressing, and perhaps solving, the pressing crises that face the United States and the world. Biden need not agree to every demand from progressives, but unlike Johnson, he will need to maintain their help in the coalition that brought him the presidency. In showing what not to do, the example of predecessors such as LBJ helps to create space for more constructive models moving forward.

WHAT CAN THE NEXT PRESIDENT LEARN FROM HISTORY?

Lessons from top advisors during the Reagan, Bush 41, Clinton, Bush 43, and Obama administrations

December 11, 2020

Watch this panel discussion from September 2016—before President Trump came to the White House. In it, senior White House domestic policy officials from five administrations offer their unique perspectives on what the future president can learn from history—lessons that also hold true for the incoming administration in 2021.

KEEPING HIS PROMISES?

Kathryn Dunn Tenpas and Nicol Turner Lee write about Black presidential appointments in the Biden administration

December 7, 2020